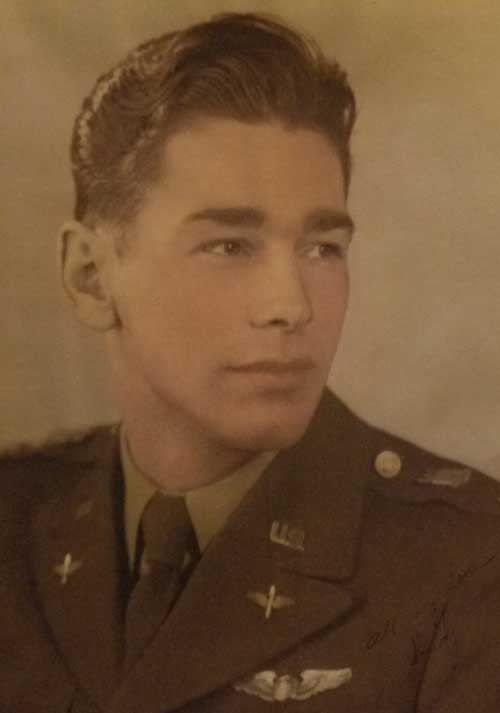

Sandy Groendyke joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1943

Sandy Groendyke joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1943 and served as a B-17 Bomber pilot in Europe. After his plane was hit and was forced to land, he was captured and held in a German prison camp for nine months.

In 2019, Sandy Groendyke told his story:

“I finished high school in 1939 in High Bridge, New Jersey. I moved to Newark and roomed with the world champion of free-flight model airplanes. We would build model planes and go to meets on the weekends. We decided to attend Casey Jones School of Aeronautics at night. He was taking engineering and I was taking the ground school. And the war broke out.

“The government got us all together and said ‘We want you to quit your jobs and go to school full-time. We’ll pay the tuition and a per diem to live on. All you have to agree to is to work for the government when you graduate.’ Sounded like a good deal!

“We would gather at the food trucks outside the school. A guy says, ‘What are we doing here in this school? We all want to fly airplanes.’ So a bunch of us went down to the post office and took the initial test for cadet. It was easy. We kept going back and taking more tests.

“They sent me up to a new air field that was being built for West Point cadets. I was an electrician on the ground crew. I aced all the tests. The only problem was that the flying schools were all full and it would be about six months before there would be an opening. They said, ‘We don’t want to lose you to the draft. So we’ll put you in the reserve, subject to call. You’ll be an officer when you graduate.’”

Flight Training

“That was 1943. We went to flight training in Helena, Arkansas. That’s where I really learned to fly an airplane.

“The planes didn’t have radios. We were taught the basics of flying and were able to pass the solo test with no instructor there to help. So I soloed the plane using pilotage—using only things you can see on the ground. Highways and rivers, navigating the airplane mechanically.

“You fly to an airport, land, get somebody to sign your logbook, and fly back. That was the solo cross-country. The next flight school was in Arkansas. We learned these stalls and spins with an instructor initially, and I had practiced only once when I earned my wings.”

Meeting Mary Helen at Church

“My friend Hank said, ‘Let’s go into the town [Jonesboro] and see what it looks like.’ So we went to town, went to a movie, danced a little, and got a hotel room.

“Hank said, ‘What do you want to do tomorrow?’ I said ‘Go to church.’ I was Dutch Reform from New York City, but I knew they wouldn’t have that church there. Hank was Baptist. He said, ‘Well, how about going to Sunday School?’ I said, ‘I’m a Yankee. We don’t go to Sunday School after the 8th grade.’ Hank said, ‘We Baptists go to Sunday School to our grave.’

“There were four girls in the choir, I’d say in their early twenties. I looked at one in particular. I said ‘Boy, I’d love to meet her, but there’s not a chance in hell.’ So I put the idea out of my mind. Then she sang a solo. The service was over. We were out in front of the church talking to the locals—trying to get somebody to invite us to eat. We were in our uniforms.

“This girl comes up and tugs on Hank’s arm and invites him to the Baptist Student Union class and says, ‘It would be OK if your friend would like to come, too.’ I said, ‘Yeah, let’s do it!’

“So it turned out that she had her eye on me while I had my eye on her. Honest to goodness, it was just sheer love. Her name was Mary Helen. I got her phone number and called her every Wednesday. I hitchhiked in my uniform to see her every weekend. We called that the Arkansas taxicab. Everybody had a pickup truck—farmers.

“At graduation I gave her a ring. She had never met my family. so we hopped a train to New Jersey and spent a few days with my parents.”

A Wedding

“I had two weeks’ leave [after earning my wings]. I called Mary Helen and said, ‘What do you think about getting married?’ She said, ‘I think that’s a wonderful idea!’ It was June. Everybody had flowers in their garden, she had bridesmaids from her choral group who had all gone to high school together. So we had a church wedding and her mother gave her away. Her father had been deceased when she was six, so it was just her mother.”

Where Were You On D-Day?

“Mary Helen went with me when I was sent to Florida where they make up the crews. We got a motel. When we got up the next morning and came down to breakfast, people asked us, ‘Have you heard?’ ‘Heard what?’ ‘It’s D-Day! The invasion has started!’ So here we were. Somebody asked me later, ‘Where were you on D-Day?’ I said. ‘I was on my honeymoon.’

“I was putting my crew together. I got a co-pilot who had just graduated the week before. He had never been in a B-17, so I had to teach him to fly it. Then we went to Mississippi for six weeks training with the crew for combat. Next, we went to Savannah, Georgia, and stayed in a tourist court. We had a hot plate and a refrigerator. Two other guys in my crew came in with no place to stay, so they stayed with us. One slept in the bathtub, one on the floor.”

Heading to the War in Europe

“We picked up a brand-new B-17. We had orders to go to Labrador. Our next destinations were Reykjavik and Wales. We were there till October 2, then we flew over Germany.

“I had a seasoned crew. I took the co-pilot position so I could experience combat. The pilot was from Trenton, New Jersey, which was only 30 miles from where I was from. So we became good friends, of course.

“The pilot would be in control of the plane for 15 minutes and then the co-pilot would take control for 15 minutes. This was to minimize fatigue and stress. The Germans were pretty good at shooting at us. The first day, we took some flak. The crew said, ‘Oh, that’s usual.’”

Direct Hit Knocked Out Two Propellers

“On our second day, October 3, our target was Nuremberg. But we took a direct hit which killed the bombardier. The propellers on each side of him were knocked out, so we ‘feathered’ the props. We kept the two other engines running part-time but never at the same time. It was a hard thing to control, but it allowed us to get a little farther away. We were at about 24,000 feet when we were hit.

“We knew we couldn’t get back to England. We knew the nearest friendly was Switzerland. We kept going down and down and down.

“At about 12,000 feet we called our crew in the back and said, ‘Anybody wants to bail out, do it now.’ They called us back and said, ‘We’re with you. We’re going down with you.’

“We had opened the bomb bay doors so the crew could bail out if they chose to. We didn’t know this until several days later, but one guy picked up a parachute. The others asked him, ‘Where are you going?’ He said, ‘Getting the hell out.’ They said, ‘No, you’re not.’ They took the parachute and threw it out the bomb bay door. So they made him stay with us.”

Emergency Landing

“We were northwest of Munich. We went down through the cloud cover and saw the most beautiful farmland. Beautiful. So we started looking for a field to land in. This little town was maybe 30 houses or so. The wind was just right. We had been trained to check the wind by finding smoke or clothes on a clothesline—to see which way it was blowing.

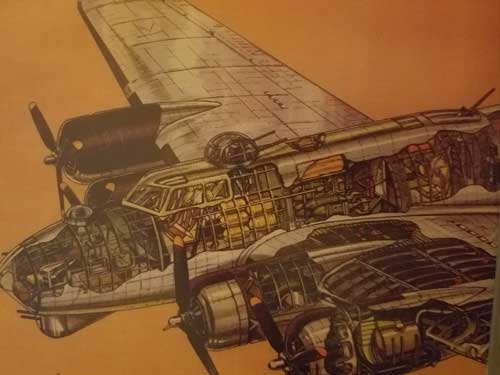

“We went through a fence when we landed. It blew apart like toothpicks. That broke the plexiglass nose cover where the navigator and bombardier sat (drawing at right). The bombardier, who was dead, fell out.

“The people on the ground were harvesting grain. Everything was done by hand, with a scythe, no machinery. They were starving, the German people.

We Had Bombs But No Guns

“While we were circling the field to land, they saw us. They went off to the sides to wait for us to land. We got out of the plane calmly. We didn’t have any guns. We had thrown everything we could off the plane to make it lighter. We had bombs but no guns. The people had guns, so there was nothing we could do. They had guns to protect their food. People were starving. So they took us to the village and put us in a building.

“We went back there 30 years later and got this picture.”

“We didn’t know it at the time, but this was a 14th century building that had been used by farmers to store their property. There was no law enforcement back then, so they would put their food in this building to secure it. That’s where they held us.”

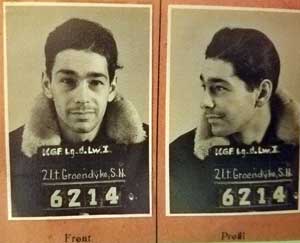

Sent to a German Prison Camp

“We were kept in that building [in the farm land] until nightfall, when the Luftwaffe came in their ‘six-by’ truck—a truck with a canvas top. There were nine of us prisoners, everyone except our bombardier who had been killed. They took us to the Luftwaffe base, probably 150-200 miles from where we had landed. They treated us like gentlemen. We offered no resistance. We were fliers, not fighters.

“They took us to their base and gave us a nice meal and bunked us down. It was on the floor but had some straw ticks we could sleep on. They gave us breakfast. Guards took us to an interrogation place on the Mainz River. It took us three days to get there. They took us to a stone building. No heat, of course. Individual cells, we were in solitary. They’d give us soup for lunch. One meal a day, we got. It was lousy.”

Interrogations

“They would interrogate us one by one. They tried to get information. All we would give them was our name, rank, and serial number. They tried to lure you in. Those days, everybody smoked. They had cigarettes they would offer. Where they got them, I don’t know, but they had them.

“They put us on a train and sent us way up to their prison camp on the Baltic.”

American Officers Ran the Camps

“The camp was actually run by our American officers. They were prisoners. I happened to be in the barracks where the ‘wheels’ were. Their function was like this: if the Germans wanted something done, they had to talk to our senior officers, according to the Geneva Convention. So then the American officers would tell us to do it.

“We had to go to roll call twice a day. The first one was at 6:00 in the morning. So we would line up and the German would count noses. Then we started playing tricks on the Germans. We had one real short guy. We’d get him to stand at the end of the line where they always started counting. Then after the German moved down the line, the short guy would stoop down and run behind the line and stand at attention at the other end. So the German would end up with one person too many. Then they had to count all over again. We’d play games like that, a bunch of GIs.”

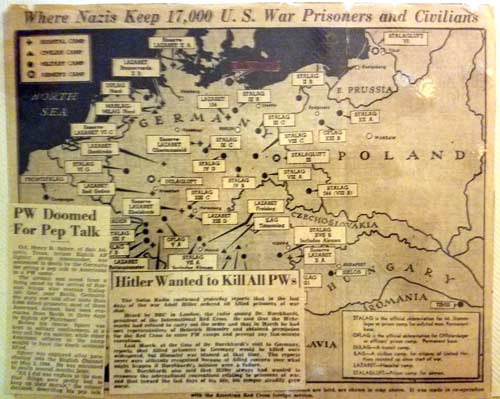

Hitler’s Plan for POWs

“We had a real mouthy ace there who was sentenced to die, but the death sentence was never carried out. You know, Hitler protected the POWs because his game was to trade the Allies’ POWs for his German officers.

“We were out on a little peninsula. There was a flak gunner school out on the beach. They were shooting at our planes and training high school girls to shoot those flak guns. The girls would ride bicycles to get to the guns.

“When the girls would come, somebody would call out, ‘Here they come!’ We would all run over to the fence and make catcalls. And the girls would start flipping their skirts up in the back, just teasing us. It’s the same the world over.”

“In our camp alone, we had just under 10,000 Air Force officers. Just officers. It was near the town of Barth, right across the open water from Sweden, who was neutral. That’s where the Red Cross parcels would come in through Sweden.

“They put the Red Cross parcels on a boat and sent them over. They asked for volunteers to go down and unload them. Sure, anything to pass the time. We jumped at the chance. All the things in these parcels were helpful when we were liberated.”

Trading Cigarettes for Parts to Build a Radio

“We had our own underground newspaper, believe it or not, that the Germans never found. Some guys who knew how to make a radio would trade American cigarettes with the German guards for all the different parts they needed to make a radio—a secret radio.

“They got it working and would listen to the BBC. Somebody would type the news down on a piece of paper and we would pass it around after dark and read by oleo lights. Just one copy passed around.

“We used oleo [margarine] to make lamps. We had small tin cans that powdered coffee came in. When they were empty, we’d use those cans to make our lamps. We melted oleo on the stove in those cans and put a wick in it there made with a piece of cloth cut from the hem of our pants and a wire. Then we let it harden.

“That gave us lamp light. We used those lamps to read after 9:00 pm when they turned the lights off.”

The Allies Landed and Were Coming Toward Us

“The war was starting to end. The Allies had landed and were coming up through France. The Russians were coming like a vise. We were right in the center line.

“The Germans didn’t know where to march us. South of us, POWs in those camps were marched toward the center to keep out of the action. This was March, freezing weather. I was so lucky. I didn’t get a scratch the whole time. I couldn’t even get a Purple Heart—thank God.”

Liberation by the Russians–a Drunken Mob

“We were in that prison camp for nine months. We knew the Russians were coming because the Germans were burning all the records. We knew the they were only a day’s march away because the German guards left the towers and put American officers in the towers.

“The Russians reached us first, before the war was over, and liberated us. They were a drunken mob. They would push their sleeves up and show us a half-dozen watches up their arms they had stolen from Germans. They wanted to sell them to us. ‘Take your pick’, they told us. We weren’t interested. They said, ‘Schnapps. Ya, ya!’ They were acting wild.”

Not Enough Boats to Take Us All Home

“In three or four days we flew out to France, across the Ruhr Valley, and saw the Cologne Cathedral. It was the only thing left standing around there.

“They took us to Camp Lucky Strike in Normandy where the troops came in during the D-Day landing. We found out that it would be a month before we could leave. There were so many troops they had to get back. There weren’t enough boats.”

Waiting in France

“A buddy of mine said, ‘Let’s go to Paris.’ But we couldn’t get a pass because they had such a food shortage in Paris. So we just asked for a weekend pass and got it.

“We went out and hitched a ride with a truck heading toward Paris. We didn’t know if it would be MPs who might arrest us for being AWOL. Turned out they were doing the same thing we were doing—sneaking off to Paris. They told us they go to Paris every weekend. So we had picked the right truck!

“One of the guys said, ‘You can stay where we’re staying.’ When we got there, we left the truck and got on the the subway to go into the city.”

AWOL in Paris

“When we came out of the underground in Paris, we were right under the Arc de Triomphe. We were so lucky. They walked us over to the place where they were staying.

“We went in and realized it was a whorehouse. The guy introduced us to the Madam. We had something to eat and then the girls magically came out and we had a party.

“We had just come out of a German prison camp and now we were partying with girls in Paris! We didn’t care.

“We couldn’t go into the restaurants because the MPs had orders not to let American soldiers in. But the Red Cross had coffee and donut stands all over Paris. So we lived on coffee and donuts three meals a day.

“Then we met a guy at the donut stand who told us the ‘wheels’ had taken over the biggest club in Paris. He knew one guard who didn’t enforce the rule about not admitting enlisted men, so we went there and got in with no trouble. We went back at the same time most days and had a good meal.”

If You Were Wearing a Uniform, You Were King

“The Red Cross had a place downtown where you could get free tickets for everything. We got Folies Bergere, Versailles, the Louvre, and a couple of shows. If you were wearing a uniform, you were king.

“Eventually we got tired of all this luxury and decided to go back to Camp Lucky Strike. I tell you I’ve had a good life.

“When we got back the officer dressed us up and down and said he could court martial us. He thought a minute and said, ‘Oh, hell. Forget it. I’d do the same thing!’

Back in the States After the War

“Mary Helen and I stayed at my father’s place in High Bridge, N.J. for a while. I asked for a transfer to Denver, known as the country club of the air, and got it. For a pilot, that was heaven. Mary Helen had her degree and worked as a teacher.

“Our daughter, Sandra, was born there. My dad was ready to turn his insurance and real estate business over to me. We had a son, Tom.

“We moved to North Carolina when we retired in 1986. Sadly, Mary Helen passed away in 2007.”

Thank you for your service, and for sharing your experience.

My cousin, Joseph Leo Corrigan, a navigator, was shot out of the sky in Oct or Nov 1942 over Belgium. Some crew members survived and were POW’S. I would appreciate any information about him. Please email me at joecorrigan0411@gmail.com

My thanks, Joe Corrigan

Thanks for info; I’m trying to find acknowledgement of my dad–possibly shot down at about same time. I believe he was the pilot. He with surviving crew to spend rest of war in German Prison camp. They grew their own food but don’t believe they were treated. very nice. He would not talk about his experiences to family and died at home at young age of 52.