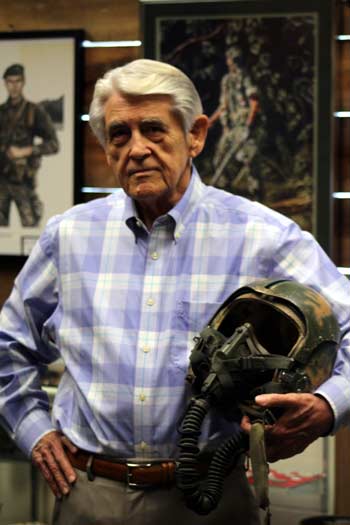

John Barker served two tours in Vietnam in 1967 and 1972, flying  bombing raids in F-4 Phantoms in the Hanoi area. Below, in his own words, is Barker’s Vietnam story.

bombing raids in F-4 Phantoms in the Hanoi area. Below, in his own words, is Barker’s Vietnam story.

I received my commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in May 1965. A year earlier I had graduated from Duke University and had been accepted into the Air Force’s Officer Training School (OTS) as a pilot candidate. Following a year of pilot training at Moody AFB, Georgia, I received my wings and was assigned to George AFB, CA, for qualification training in the F-4 Phantom II, with a follow-on combat assignment to Vietnam.

The F-4 is a Mach 2 fighter-bomber with twin afterburning jet engines, and is capable of carrying a formidable array of bombs, rockets, missiles, cannon, and other unpleasant stuff. It’s a highly complex, versatile, demanding machine, and built like an airborne tank. It carries a crew of two, seated in tandem cockpits.

The war in Southeast Asia was increasing in intensity at this time, so there was a sense of urgency in getting us trained for combat as quickly as feasible. Our instructor pilots at George had recently returned from combat duty, so we profited greatly from the “pearls of wisdom” they passed on to us.

The front seat pilot, or Aircraft Commander (AC), trainees in our class were more senior officers with many years of flying experience, particularly in other fighter aircraft models. Newly-minted pilots were basically in a co-pilot role in the aft seat until we gained enough experience and training to upgrade to the front seat. We were affectionately known as GIBs — Guy In Back. As GIBs we spent most of our time operating the radar, weapons, and navigation systems which gave the F-4 its awesome attack capabilities.

Upon completing the flight qualification course at George, we received our combat assignments. Mine was to the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing (the “Wolfpack”) in Thailand. We were given about a week of leave prior to departing the States, so I made good use of the time by courting a young lady named Helen from Los Angeles I’d recently met.

I arrived at Ubon Royal Thai Air Base in February 1967. Our Wing Commander was the legendary Colonel Robin Olds, a ferocious fighter pilot and World War II Ace, who was as inspiring a leader as any young aviator could have wished for. My AC, Captain Joe Higgs, and I were assigned to the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron, the “Triple Nickle.” It was Air Force policy then that once a pilot completed 100 combat missions over North Vietnam his tour was complete. The trick was to reach this number while still in one piece. Sadly, many of our squadron mates didn’t make it that far.

The most common missions, and the hairiest by far, were the bombing raids we made into the Hanoi area, reportedly the most heavily defended territory in history. These strikes typically involved twelve to twenty aircraft, each armed with air-to-ground ordnance, air-to-air missiles, extra fuel tanks, and various other hardware items. Preparation for each mission required several hours of target study, pre-flight briefings on weather, intelligence, enemy defenses, weapon settings, delivery parameters, and so on. The amount of planning detail involved for each flight was extensive, but critical to mission success.

Following the briefings, each pilot collected his gear – survival vest, anti-G suit, flight helmet, sidearm, extra water flasks, etc. – and reported to his assigned aircraft on the flight line. After a thorough walk-around inspection of the aircraft and ordnance, we strapped into the cockpit, and stood by on the radio for engine start time. With both engines up and running and generators on line, we checked all systems to make sure the aircraft and weapons were operating as expected.

Once the entire strike force had started engines and taxied to the runway for takeoff, things got pretty serious. For anyone in the vicinity of the runway the noise level became deafening – imagine the Daytona 500 on steroids. Takeoff was made in two-ship, or “element,” formation, hustling down the runway in full afterburner, accelerating to a lift-off speed of about 160 knots. Two elements would then join up in the air as a four-ship “flight.” Each flight of four circled the airfield in close formation, joining up with the other flights, until the entire strike force was formed. Then the whole gaggle climbed to altitude, headed for the airborne tankers, and proceeded with air-to-air refueling. Topping off the fuel tanks as close to the target area as possible was vital, just in case we had to hang around after the strike for longer than expected.

Flying a jet fighter has been whimsically described as “hours and hours of boredom, relieved occasionally by a few moments of stark terror.” That’s never truer than when the enemy starts shooting at you, as normally happened during interdiction missions against an enemy airfield or munitions factory in the Hanoi area. On rare occasions, we’d enter the target area without opposition, and the raid would go off without a hitch. Most of the time, however, the North Vietnamese would interrupt the strike force with ground-to-air defenses or by airborne intercept with their own fighters. Then all hell would break loose.

To complicate things further, the dive bomb maneuver requires intense and total concentration for fifteen to twenty seconds after “rolling in” on the target. About six parameters (dive angle, air speed, release altitude, etc.) all must be met at precisely the same instant that weapons are released, or else the bombs will probably miss their target. During these few critical seconds, the aircraft is most vulnerable to enemy fire, so the adrenaline rush is at a peak. If just prior to, or especially during, the dive your aircraft was in imminent danger of being hit by air defense artillery or a surface-to-air missile, the wisest move was to break off the attack in favor of saving your own you-know-what.

The commie gunners, of course, knew this very well. This required that you jettison your bombs and any other external stores, break away from the pending threat, ignite the afterburners if necessary, and immediately begin a series of twisting-and-turning, erratic changes in altitude and direction known as “jinking.” It’s not very comfortable. If the threat were enemy fighter planes, on the other hand, the occasion called for switching to air-to-air combat mode, or a “dogfight.” This rare opportunity, by the way, is what every self-respecting fighter pilot lives for. I only had one such encounter, but since we were really low on fuel, and the MiG was flying down in the weeds where enemy ground fire was a threat, we had to break it off and postpone our day of fame and glory.

Following the delivery of all ordnance by the strike force, it became a matter of reassembling from our scattered locations around the target area and heading for home, or, in the vernacular, “getting the hell out of Dodge.” Each crew eventually rejoined its element, two elements rejoined as a flight, and flights rejoined the strike force, all while traveling at warp speed, trying to avoid enemy defenses, and chattering on the radio to determine everyone’s status. To a casual observer, this post-attack scene would have probably looked like absolute chaos. But this “max performance,” high-speed egress dance is exactly what the pilot delights in, and it’s how fighter aircraft are designed to perform. The pilot is unleashed for a few incredible moments, and he is given leave to fly like a madman. He may briefly put aside the strict discipline of formation integrity, get some compensation for many monotonous hours of straight-and-level flight, bear his fangs, and take his powerful aerodynamic machine through its paces.

If a crew had taken a severe hit and had to bail out, we tried to pinpoint the exact spot where their parachutes landed in case a search and rescue operation was feasible, or at least to visually confirm that, in the best case, both crew members had “punched out” of their crippled aircraft successfully. Seeing a squadron mate shot down over enemy territory was the gut-wrenching event that each of us dreaded the most, for understandable reasons.

As frequently happened, however, a stricken aircraft might be coaxed out over the Gulf of Tonkin before it gave up the ghost and had to be abandoned. The crew could then eject over the water and reasonably expect to be rescued almost immediately. The F-4 was tough enough in many cases to stagger all the way back to base and land safely, even after suffering seemingly catastrophic damage.

But if all turned out okay, and once we were reassembled into formation and safely out of harm’s way, the strike force joined up with the KC-135 tanker aircraft for a second refueling. Flight suits were soaked with sweat, muscles ached from high G-force maneuvering, and throats were dry, but we were finally headed home.

Not surprisingly, there were occasional episodes of comic relief. One of my favorites was the day Lt. Bill Harding was initiated into the fraternity. On his first mission, Bill got shot down. Luckily, he managed to limp out of enemy territory and eject over the water, where he was soon rescued. He is credited with coining the phrase, as he descended in his parachute, “Sweet Jesus! Only 99 more to go!”

After safely landing from one of these exhausting, four-hour-long missions, and following the post-flight debriefings, we usually made a bee-line for the Stag Bar, the location of choice for relieving the day’s stress and swapping war stories. If all had gone well, and if each flight had returned without casualties or losses, the celebration was understandably festive. Needless to say, if a crew had scored a MiG kill, the ultimate prize for any fighter pilot, there was absolute bedlam.

It took me eight months to reach the magic goal of 100 missions, and in October I completed my combat tour. I was reassigned to Yokota Air Base, Japan, for a three-year operational tour in the F-4, this time as an Aircraft Commander. Helen and I were married during this tour.

In 1972, I returned to Ubon for another combat tour. There had been a dramatic shift in the combat environment from when I was there last. The most significant change was in the sophistication of the tactical weapons we were now using. New state of the art laser-guided delivery systems and “smart bomb” technology had replaced the former generation of ballistic ordnance, and precise, surgical strikes against virtually any target were now the norm. Improved radar and heat-seeking guidance on our air-to-air missiles ensured much greater reliability and effectiveness in virtually any environment.

Even the formidable North Vietnamese missiles and AAA (anti-aircraft artillery) weapons were increasingly vulnerable to our jamming and interdiction systems. We had attained unquestioned air superiority from the very beginning, so enemy aircraft were normally not much of a threat to our strike forces. Bombing operations continued but not on the scale of earlier years.

The former 100 mission policy had been changed by this time, and the required tour length was now one year. Rumors of pending peace negotiations began to spread, and it soon became evident that air operations over North Vietnam would soon come to a halt. I completed my tour in February of 1973 at about the time the Paris Peace Accords were being signed, and received orders to 9th Air Force Headquarters at Shaw AFB, SC.

There are few things more exhilarating and memorable than what I experienced in Southeast Asia, and I made it home in one piece, so I have a lot to be thankful for.

Barker retired in 1985 as a Lieutenant Colonel. In addition to his F-4 and other aircraft assignments, he was an F-16 instructor pilot and squadron commander. Among his decorations are the Distinguished Flying Cross with three oak leaf clusters and the Air Medal with seventeen oak leaf clusters. He and Helen celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in June.

In collaboration with writer Michel Robertson and the WNC Military History Museum, The Transylvania Times will publish an article once every two weeks on a local veteran who served in Vietnam.

Article first appeared in The Transylvania Times July 2, 2018

Wow

LT. COL ( AF Retired ) John Barker more than likely knew my father, COL ( AF Retired ) T.E. DORRIS, as he was also stationed in Ubon during the same time, flying the same missions. Even though my father passed away two years ago, I still find myself looking into his history during his time in Vietnam. I hold those that sacrificed their lives during this time in highest honor and am extremely proud to mention my father and the fact that he fought ( fighter pilot ) in Vietnam and Korea, where he accumulated over 140 missions during several tours.

Thank you to all Air Force pilots and Naval Aviators for the willpower, courage and dedication that embodies the American fighting spirit. You have always proved, at great risk, and often loss, exactly who you are and what you do do so well.

As the son of a WW II Army Air Corp pilot and nephew of an A4 Aviator, I hold these men and women in the highest regard. God bless you and the United States!

Yes this was a fantastic aircraft. I trained at George Air force base also but as ground crew, Crew Chief f4c, f4d and in Vietnam F4E. I loved this aircraft, also known as THE FLYING BRICK. Ispent 6 mos in Cameron bay and then 6mos in DaN. o

ag. our pilots keep us safe so we could eventually get to go home in one piece. I feel lucky unlike others that didn’t. We all fought to keep this country of ours safe. LAND OF THE FREE CAUSE OF THE BRAVE.

Thank you for your service, and for reading our veteran’s story!

M. Robertson

Veterans History Museum Board Member

I was an F-4 electrician at Udorn, Thailand in 72 and 73 with the 432nd FMS squadron. I worked on F-4s 12 hours a day. Col. Barker referred to peace talks in 72 & 73. Operation Linebacker II occurred in December 72. It was an all out bombing campaign to end the war. North Vietnam agreed to our terms and signed a peace agreement, effectively ending the war.

Steve Richie became an Air Force Ace in 72 flying tail #463 which is on display at the USAF academy. I worked on that plane several times.

Lt Col John K Barker was my high school friend. He was Senior Class President of Fort Lauderdale High School, 1960. From the time I met him in sixth grade, you could tell that John was a leader and one who was destined for great things. He was and still is unassuming, but he had a presence and character that made him stand out. It is not surprising that he was a many decorated Air Force pilot who served his country during a horrific war and beyond. After 100 missions plus, I would have to say that God was his copilot. Thank you for your service and friendship. Keep in touch.

My brother: Steve “Maddog” Magner flew the F-4 in Vietnam and made it back home in one piece . . . thank God. What an amazing experience. His son is now protecting our nation in a B-2 bomber, so now you know how the legacy continues.

My dad, Richard (Dick) B. Whittington went to Ubon as an F-4 pilot in January of 1967! I am hoping you remember him. I really enjoyed your article. Thank you!

Thank you Lt. Col Barker for this excellent account of your flying missions for the USAF in 1967. My dad, Richard (Dick) Whittington was an F-4 pilot at Ubon with you. He was badly burned in a tragic accident on May 9, 1967. He survived, thrived, and we enjoyed him for nearly 50 years until he passed away from complications due to Alzheimer’s. Dad loved to fly, loved his career in the Air Force, loved his family, and loved our country. He was a remarkable man.