Harold Wellington (in Merchant Marine uniform) served in the Merchant Marine from 1942 to 1946, the U.S. Army in 1948, and the U.S. Navy from 1950 to 1954. He served in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

A Young Man in Vermont joins the Merchant Marines

Harold Wellington tells his story: “I was living in Brownsville, Vermont. I tried to join the service before the war when I was 17 but my dad wouldn’t let me. He wouldn’t sign the papers. But when I turned 18 in 1942, I went down to Massachusetts to join the Navy. Back then, they didn’t have recruiting offices in every little town. I had to go across to another state.

“I’d always had my heart set on going into the Navy. Back then, everybody was joining the service. The Navy said, ‘We can’t take enlistments. We’ve got too many people. You’ve gotta go through your draft. And when you go through the draft, they’ll put you where they want you—wherever they need you.’ I was working on a farm for $25.00 a month and my keep. Farm help was deferred, so they probably wouldn’t have drafted me. So I didn’t want to go through the draft and be put into the Army.

“I saw this place that said ‘Join the Merchant Marine.’ Being non-educated, right-off-the-farm, all I knew was that they went to sea, and that’s what I wanted. They sent me to Brooklyn, New York to boot camp. I didn’t realize that the Merchant Marine wasn’t classed as a service. Even though it was a civilian job, it got you deferred from the draft.”

Merchant Marines boot camp was run by the The Coast Guard

“The Coast Guard ran the boot camp for the Merchant Marine. All we did was learn military history, protocol, and learned how to abandon ship and row life boats. They sent me aboard ship and showed me where the fire room was. They said, ‘You are now a fireman and water tender. You’ll be here for the next eight hours on duty,’ then turned around and walked out.

“No training, no nothing. I’d never seen a boiler in my life. As a result, I had to learn everything all by myself. This valve does this. This valve does that. You just figure it out after a while. We always traveled in convoys escorted by Naval Destroyer and British Corvettes. Of course, we were always escorted by the German subs, too,” Harold laughed.

“First we went to Galveston, Texas, but I don’t know how we made it past the North Carolina coast because they were blowing up ships like crazy down there. My first trip in early ’43 was to London while the Germans were bombing England. You could hear them coming. We were taking war supplies to our troops in Europe.

“Then the next ship I got on, we went to the Mediterranean, down through the Suez Canal, into the Indian Ocean, and over to the Persian Gulf. By that time, the lend-lease supplies to Russia were going by rail because, previously, going by ship to Murmansk, Russia, was a death trap. If half the ships made it there, they were lucky.

“The Army had built a railroad from Iran to Russia, which nobody knew anything about. Or the Germans knew about the railroad, but they were busy somewhere else. So that’s where we took the supplies—to Iran. So we could get supplies through to Russia that way. The chance of losing our ships was much smaller going to Iran than to Murmansk.

“Then I made a second trip to Iran and Iraq down the east coast of Africa to South Africa. Then we went back up into the Suez Canal to Italy and North Africa. Our troops had got out of Africa by then and were fighting in Italy. We were picking up armaments from Africa and taking them to Italy or bringing them back to the States.

“We had been in Bari and Taranto, Italy when we heard the rumors of the D-Day invasion. We were hearing scuttlebutt that it was coming—rumors. We unloaded supplies in Italy and we all held our breath, wondering what we were going to do when we left Italy. Would we go to France for the invasion? But they sent us to North Africa to load up scrap metal. We knew we were on easy street then because we wouldn’t be taking scrap metal to France. We had been back in the New York six days when D-Day came, so we missed it by six days. We were lucky.”

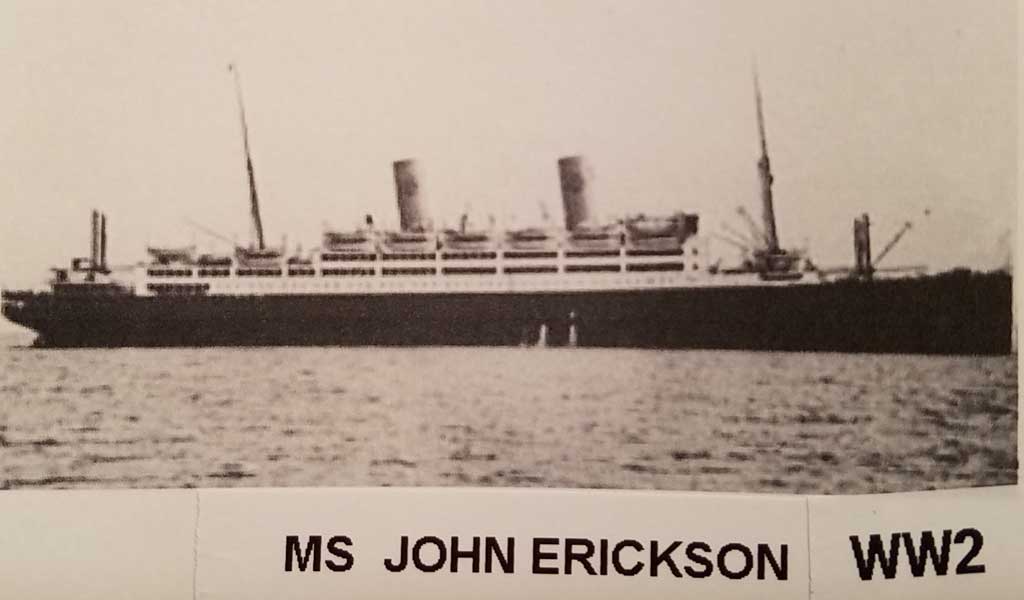

“We had a Swedish ocean liner (cruise ship MS John Erickson, shown above) that had been converted to a troop transport. I made two trips to France on that ship to bring our troops home after the war. They were liberating prisoner of war camps in Germany and we were bringing our troops home. I was an oiler in the engine room. The Army had medical treatment facilities on the ship.”

Asked how it felt to be bringing these POWs home, Harold said, “At the time, you were glad, but you don’t think much of it. You’re just doing your job. But later on in life, you realize what it was. It was so great.”

“I got on a Liberty ship and went to Portugal and France. I was in Marseille, France on V-J Day. We weren’t supposed to go off the ship after 10:00 pm, but we went anyway. We went ashore and bought up all kinds of wine and booze and brought it back to the ship to celebrate.

“I went through the whole war in the Merchant Marine and got out in 1946 as a licensed fireman, water tender, and oiler.”

Surprise: The Draft Board Called

“When I left to go into the service I told my dad, ‘I ain’t never coming back to the farm. I’ve played nursemaid to cows as long as I’m gonna.’ So when I came back to Vermont in ‘46, I went and got a job in an auto body shop.

“In 1948 the Army called me and said, ‘You’ve never been in the service.’ They went and drafted me into the Army. I’d been through the whole war in a service that had the highest fatality rate except for the Marine Corps, because of the sinkings of our ships by German air strikes and submarines. Hell, we were getting blown all to pieces. And they say, ‘You’ve never been in the service.’

“So I spent a little over a year in the Army, which I hated. After a little over a year, they said, ‘We’re not going to discharge you. We’re going to release you for the convenience of the government. But you’re going to spend six years in the Reserve.’”

In the Navy, Finally

“I came home from the Army. Seven months later I got a letter from the draft board and was called back in. But there was no way I was going back in the Army because I hated it. So I went back to the Navy office. This time they said, ‘You join the Navy and we’ll get you released from the Army.’ So that’s what I did.

Revised for SEO: “I spent all of the Korean War in the Navy, but not in Korea. Then stationed on the East Coast of the U.S., traveled to Copenhagen, Denmark and Lisbon, Portugal as a Second Class Boilerman and was discharged in 1954.

“Then I came back home and went back to work in the auto body shop. I did that for most of the rest of my life. In 1988, the government declared the Merchant Marine a part of the Coast Guard. I received an official discharge from the Coast Guard and the benefits that went with it.

“After I retired, I was in South Carolina with a national camping club. That’s where I met my wife Martha—camping. I was 66 years old and got married for the first time. She had two children who were still living.

I was lucky to have these two stepchildren, who took me in and have been great to me. Martha and I lived in Brevard since 1989, which was her home. She passed away in 2015.”

In retirement, Harold has made hundreds of wooden toys which he donates to children through a home for battered women, the sheriff’s department, and the motorcycle veterans’ toy drive. He keeps small handmade toys in his pocket. When he goes to restaurants, he gives the toys to children.

Great story Sir. I also was a BT Snipe in the Navy during the ’70s. Traveled some of the same miles as you. Thank You for ALL of your Service.

Thank you for telling your story. My dad was Lt. Cornel in the merchant marines. He served in the Atlantic and Pacific in WW II and Korea. His ship was torpedoed three times. The merchant marines are the truly unsung heroes. His name was Warren Chester Eitelbach.

My grandfather, Norman Franklin Knowlton, served in the Merchant Marines during WW II I believe from 1937 – 1945. He once told me about the time he was asked to steer the ship through the Suez Canal because the captain was sick and the next one lost his glasses. He said that is when he knew he could “do something”. He also told me that on D day he was on a ship that had just dropped off supplies in England. Thanks for all who served.

Thank you for posting this photo. My father sailed to Italy on the John Erickson. I’ve been told that hey sailed from Liverpool 26 Oct 43, landed in Naples on 6 Nov. He was a Canadian, under 5th Div HQ in a small group called the Divisional Maintenance Area (DMA). To this day, what their role was in support of the 5th in unclear.