Don’t Ask That Question

by John Hallimore

Veteran’s Creative Writing Workshop

4th meeting, February 17th, 2016

Coming home from Vietnam to America amidst college sit-ins, peace protests, passionate political debate, and random cultural turmoil is not a fond memory. My generation, the baby boomers, turned our country upside down. The home scene, in many respects, was more chaotic than the war zone that I just left.

A Primitive Desire to Survive

My senses were keenly honed, similar, in my mind, to what a panther or other wild animal may possess. An acute awareness of surroundings is the combat soldier’s natural state of mind; when at its best, having the ability to accurately attack or defend within a split second. After spending a year in a combat zone, my responses were instinctual. The disciplined soldier’s prime motivator was a basic primitive desire to survive. It didn’t matter where, when or what, if I were awake or asleep, when the switch was flipped, I was full on.

Wow! Some adjustments are needed; 28 months after graduating from high school, I returned to a much different civilian life than I remembered. Nothing is the same as I realized, the differences included me.

An Onyx-Handled Knife on the Headboard

Returning to my parent’s home, I warned that they should never come into my bedroom without announcing their presence at the open door. On the bed’s wooden headboard, I placed a large onyx-handled knife within inches of my grasp. It was a knife that I bought in Mexico as a teenager. I never had much use for it when I was younger; I just thought it looked cool. It had a carved design with the word “Mexico” on the large and sharp steel blade. The handle was “D” shaped; onyx covered the straight part of the grip and modified brass knuckles wrapped your clasped fist……. just in case you were going to get into a fist fight (and not stab the opponent?)

When I was a teenager, the knife ended up in a box in the closet. I had not much use or desire for viewing it. I had a passion for sports and loved working on cars, not playing with knives. But now, my knife was close by with the perceived purpose of my night time security. You may think this is strange behavior . . . and now, I know it was. But decompression time was needed when readjusting to civilian reality.

For a slice of time about 15 years ago, I worked with a Vietnam combat Veteran named Luke, who was a brick mason. He was tightly wound and partially broken. I recognized and felt his pain. I recognized him as part of an elite group — he had been there; I liked him.

Construction Lunch Break Talk

In the afternoons, he would start getting tired, yet more animated. His tiredness came from the nightly ritual of getting up two or three times for his perimeter night patrol walk in and around his home. That was his guard duty. He never quite adjusted after returning to the States, but fortunately his wife and children adjusted to the many years of knowing he was on night patrol. Luke was jittery, always looking about quickly. He was tense and couldn’t quite leave the war behind. He was a pretty decent brick mason but would noticeably display greather stress as the job progressed. It seemed that about every two weeks, he would head up the mountain to the Reno VA hospital for a two day treatment. When he came back, he was OK for a while. At our construction lunch break, we would talk about getting a “Slick” (Huey helicopter) to one day drop him off on the top of the hill above the house. We all would then run to the big bird and finally “Welcome him home.” I know he liked the idea. He needed the war to end.

Free Love and “Stopping the War”

When I joined the Army, my generation was on a path in the opposite direction. The word “Hippy” came into being about that time. Guys were wearing their hair really long. The women’s movement had begun. Drugs were being touted as mystical and used everywhere. Angry heavy metal music became popular along with music that had lyrics with a cause or desire to change the world. Remember Dylan, Donovan, Country Joe and the Fish. Free love and peace were the mantra with an importance placed on “stopping the war.”

Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30

Question the establishment and “Don’t trust anyone over 30”. It seems as though half of the generation was traveling around in VW mini-buses following the Grateful Dead or looking for the next big “Peace Event” or wild assembly out in the countryside; events such as Woodstock. It was a giant party with booze, drugs, free love and marijuana-induced enlightenment, discussion of world events (Vietnam), creating a new cultural labyrinth veiled in heavy fog.

The contrast was too sharp. My world shaped during a year in the jungles of Viet Nam was nothing like the world that I came home to. Always looking forward, I felt positive about going to college on the GI Bill.

I Had to Adjust, I Needed to Blend In

The skills I learned in combat had no correlation or usefulness here in the States. I came home to a country that hated the Viet Nam war and certainly did not appreciate the soldiers who fought and sacrificed there. I had to adjust, I needed to blend in. My new life attending San Diego State College began during a time of regular campus war protest. Membership within fraternity houses and sororities was seen as inconsequential activity as compared to being involved in the war movement or other great cause. Many of those houses were closing up due to lack of interest.

The college administration building was fire-bombed in protest of the war, which destroyed some of the files and records. Hundreds of armed police officers ringed the building shortly thereafter. College professors were leading protests which included students lying on railroad tracks to stop the shipment of bombs by train.

There were some professors who used their class forum not for curriculum, but to advocate participation in the “stop the war” movement or for other social causes. It was generally known that student success in a handful of these college courses was based upon being radical; participating in and protesting a cause, or sometimes getting laid by the professor. It was outrageous.

How does the young, recently discharged war veteran comprehend his surroundings?

I certainly wasn’t going to volunteer information of where I had been or what I thought about Viet Nam. Just like camouflage fatigues, there was a way to look, a way to dress and a way to act if you wanted to blend in during this age of confusion. I had learned to be keenly observant when stealthily moving through the jungle on patrol. My current observations, uncharacteristic of the left-behind norm, slowly helped me with perspective and adjustment. I was serious about my education and had a desire to enjoy life, maybe it wasn’t important to fully blend in.

It Was Best to Be Unrecognizable

For the most part I understood that it was best to be unrecognizable as a Viet Nam veteran. I certainly wouldn’t openly discuss or claim that I was in combat and had taken lives. I ignored the protest and attended my classes. The few Vietnam veterans that I met in college were quiet and intent on doing well. We were members of a silent brotherhood who had fought in an unpopular war. We had survived and desired to strive in this new arena of challenge. We were close in understanding, but maintained a secured distance of individuality.

A Language of “Knowing”

It is not often that I cross paths with a fellow Viet Nam veteran. It is rare to meet a Viet Nam veteran that has shared the combat experience. But when it happens there is typically a mutual and natural affinity for one another. We share a language of “knowing.” I recognize the strength and the goodness of these brother warriors . . .and I pray for the broken ones who hurt or continue to carry too much of the load.

We were discreet. Not many knew that we served in Viet Nam. Our friends and family were generally understanding and sensitive to our personal experiences that were hard or not discussed. They didn’t ask questions, they waited for us when our time came to share. It could take years to really talk about some things, and only with those who were close or who we could trust.

“Did You Kill Anyone?”

Vulnerability that penetrates to the core can surface when digging up combat memories. Those few people along the way who were bold enough to ask questions such as “Did you kill anyone?” or “How many Viet Cong did you kill?” were typically people I did not want to share my memories and feelings with.

How likely were they to have a preconceived idea of how we should feel or how we should respond? Did they hate the war and protest the soldier? Did they watch battles on TV and see the impersonal act of a bomb hitting its target? War is not a video game; life and death are up-close and personal to the combat veterans that I know.

Does the one with the bold question have a superior moral attitude of how and what they would have done if they were in your boots? How could the non-war tempered being understand the adrenalin and confusion during battle? If I suggested that being in a fire fight was comparable to the adrenalin rush experienced by an athlete who first touches the ball in a championship game, could or would they comprehend such a feeling?

Please Don’t Ask That Question

Can the same person understand the thoughts of the mind when looking into the eyes of a fellow human being whom moments before was very alive; a person you killed but did not know and a person you realize that you do not hate? So, please don’t ask that very personal question unless you know me well. Some of these things can’t be easily shared.

For me, 46 years of perspective adjustment continues. With age, I feel a greater emotional connection and softening of the heart to the events. Memories of the war, which I lived, have never left me. I accept this.

Side Note On Music of the Time

Music is a whole world of topic in the Vietnam era. Remember Dylan, Donovan, Country Joe and the Fish. I also remember songs such as “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire, and “If You’re Going to San Francisco,” which was the song of destination home for the Vietnam soldier. “The Universal Soldier” by Donovan/Buffy St. Marie, “We Got to Get Out of This Place” by the Animals. “Paint It Black,” etc.

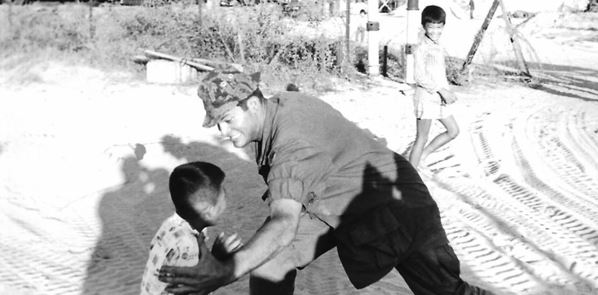

Above, Hallimore having fun with Vietnamese kids at a roadside stop

Powerful stuff. Thank you for sharing. And thank you for serving.