An excerpt from “Welcome Home, Brother: Memoirs of Vietnam War Veterans” by Michel Robertson.

Lt. Cdr. Grady L. Jackson, senior Bombardier/Navigator assigned to VA-75, an attack squadron of the US Navy known as the Sunday Punchers, arrived in Vietnam’s Tonkin Gulf in June 1972. The squadron, deployed aboard the USS Saratoga, flew the A6A Intruder all-weather night attack aircraft. The Intruder carried large ordnance loads and flew long distances. It also had the capability for air-to-air refueling.

At night, enemy radar could not track or guide the aircraft at 500 feet and below; however, that did not stop their Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA) barrage fire (which were visible because of the red tracers, interspersed in the AAA). Says Jackson, “At night the F-4 Phantom fighters, who flew Barrier Combat Air Patrol off the coast of North Vietnam, would tell us that they could follow our flight path by the AAA red tracer fire along our route as we headed to our target inland.”

One of Grady’s favorite stories from Vietnam is the daring rescue of Lt. Jim Lloyd on the night of 6 & 7 August, 1972. Lt. Lloyd was flying an A7A single-seat aircraft on an armed recon flight over North Vietnam, about 150 miles north of the DMZ. As darkness set in, a surface-to-air missile struck Lt. Lloyd’s aircraft, necessitating immediate ejection 21 miles inland.

A6 Intruders flying over Vietnam. The Intruder could carry large ordnance loads, fly long distances, and had the capability for air-to-air refueling.

The Rescue of Lt. Jim Lloyd

Jackson describes the harrowing rescue.

“CDR Charlie Earnest, CO of the Sunday Punchers, was my pilot and we took over as Search and Rescue On Scene Commander about an hour after Jim was shot down. That meant the decision of whether to try to rescue Lt. Lloyd was in our hands. By the time we arrived feet-dry over the beach, it was totally dark. However, we had received a good debrief over the radio on where Jim was located.

“Flying at 500-1000 feet, we immediately established radio contact with Jim Lloyd. However, he asked us to move away from his position due to the large number of enemy soldiers searching for him. We flew inland to coordinate the rescue effort.

“As Jim was trying to escape the fiery wreckage, he heard footsteps along the path near a rice paddy. He lay face-down in the muddy paddy and played dead. The footsteps stopped, and he felt someone poking him with a gun. When the soldiers stepped away, he jumped up and ran, bullets flying all around him.

“Almost 3½ hours had passed since Jim’s ejection and time was running out for his rescue. The Big Mother rescue helicopter had been delayed due to refueling problems.

“As On Scene Commander, it was our responsibility to make the decision whether or not to call in our AirWing helicopter, now escorted by USS Midway A7’s. Immediately the Skipper and I flew back to where we thought Jim was located but were unable to establish radio contact. I quickly radioed the rescue team and told them to hold their position, which was over enemy territory.

In desperation, I cried out a prayer: ‘God help.’ Immediately, I thought to return to the original heading and try again. As soon as we did, I established radio contact with Jim.

“We redirected Big Mother and escorting A7’s. To aid them, the Skipper turned on our outside aircraft lights so the rescue team could vector on us. However, this also gave the AAA sites an excellent target.

“Because of Jim’s weak radio, I had to relay all the radio transmissions between Jim and the rescue helicopter. All radio transmissions were also conducted on the Universal Guard Channel, enabling the whole world to hear in real time the Jim Lloyd rescue operation.

“Our USS Saratoga H-3 helicopter crew, uneasy about the terrain, turned on its landing lights to avoid a small mountain ridge. In doing so, the pilots experienced temporary night blindness, flying right over Jim Lloyd! From our bird’s eye view, I saw Jim in a rice paddy, frantically waving his arms, with North Vietnamese troops closing in to capture him. I screamed in the radio for Big Mother to make a 180-degree turn.

“Finally, amidst a giant burst of fire from a 57mm gun, the helo lowered its rescue cable with the jungle penetrator hooked to the end. Jim quickly attached the penetrator to his torso harness. As he jumped as high as he could, the door gunner grabbed him by his flight suit and threw him into the cabin with an adrenaline-fueled heave. They turned off their lights and, despite several bullet holes, they made it back to the ship.

“The Skipper and I made our way back to the Saratoga, having logged 3.8 hours of flight time that night, most of it over North Vietnam, by far the longest flight we had experienced over enemy territory!

“This successful Navy rescue was one of the deepest in enemy territory during the war. Many risked their lives to rescue Lt. Jim Lloyd. That night we showed the world that if you go down, the United States Navy will do everything they can to keep you from being captured or killed.”

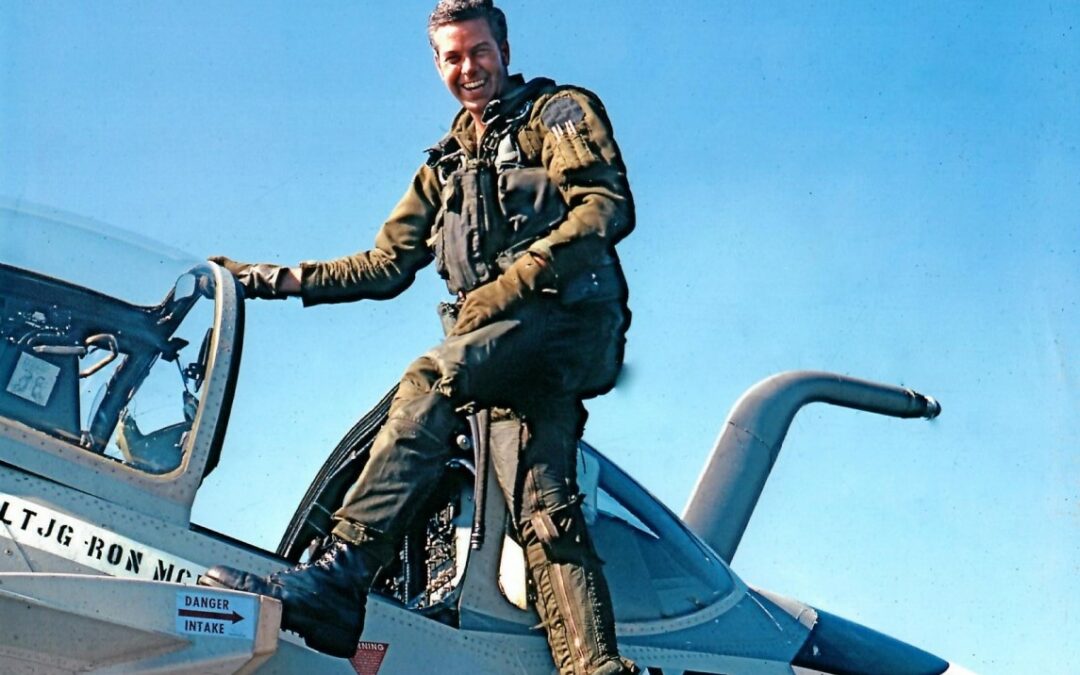

Far left, Rear Admiral Lower Half Grady Jackson. Left, Sunday Punchers patch. In boxing, the Sunday Punch is the most powerful and effective punch of a boxer. In the armed forces, it is anything capable of inflicting a powerful blow on a hostile or opposing force.

Grady Jackson, who retired as a Rear Admiral in 1991, is glad to see Vietnam veterans honored. “The Vietnam War had a negative connotation for many people. But that doesn’t negate what our veterans did. So many lives were lost for others’ freedom, so many gave so much.”

I had the distinct honor and privilege of serving with then Commander Jackson alongside CDR Jim Eilertsen, the XO and CO respectively of VAQ-134 ‘Garudas’ during our 1976-1977 cruise aboard the USS Enterprise, CVN-65.

Their dynamic leadership and sincere concern for all of the squadron personnel was one of the highlights of my naval career.

If I was asked to serve with either if them again, it would be my distinct honor.

Nick Nevels

AEC USNR (TAR) Retired

P-3 Flight Engineer

Boeing 787 Customer Training Specialist

I served in Big Mother (HC-7) from May of 1970 until June 1973. The two crewmen on the Jim Lloyd Rescue were Stretch Ankney and Matt Szymansky. Stretch is the crewman that threw Lloyd into the Helo. No small task of you have seen Jim Lloyd. HC-7 was continuously on

Yankey Station for over 7 years. Rotating Pilots & Crewmen. Had I not rotated back to Cubi I would have been on that rescue with Matt. However, we hooked back up and got three under fire rescues in November 1972. Sadly both Stretch and Matt have since died. Michael Shepherd.

Thanks for the reminder that we are different.

I hope all is well with those of us still here !

I knew Adm. Jackson on the USS Saratoga while on a med cruise and before the ship deployed to Yankee Station. We played basketball together and he arranged for me to fly off the boat in the A-6 (right seat). What a great man and cosumate warrior.

Dr/Col Jon E Schiff, USAR, ret

More of these blog posts.

One of the finest gentleman and naval officers I have ever encounted. We first met when he was a LTJG and I was an ENS. He was my EW instructor, which eventually became my life. When he was CO of VAQ-134, I was his Maintenance Dept Head.

I will add to the above comments. As a squadron commanding officer, then Commander Jackson was a superb leader. His aviation skills were honed by combat experience and his leadership style was respected by all who served under him. He cared deeply for the men he served with, and was a model for professionalism in every person no matter what their warfare specialty. Hand Salute Admiral Jackson.

Admiral Jackson was one of the finest officers with whom I have ever served, but more importantly, he was a true Christian who lived his faith. I served with then-Commander Grady Jackson during my first tour in EA-6Bs as an Electronic Warfare Officer with VAQ 134, when Commander Jackson was just taking over as CO. Later, I had the honor and pleasure of serving on his staff in the Pentagon. I do not know any other officer whom I have respected more.

I have had the privilege of living 52 years (and counting) since being rescued Aug. 6th 1972 thanks to Grady and countless other Navy aircrews who risked their futures to help secure mine.. I have been proud to call Grady my friend over the years since. I will be forever grateful to all who were there for me when I really needed it!!

– JIM LLOYD (“ZEKE”), FORMER VA 105 GUNSLINGER-