Vietnam Veterans Series

USMC Tunnel Rat Urges PTSD Victims to Seek Help

By Michel Robertson

USMC Tunnel Rat Urges PTSD Victims to Seek Help

Building tunnels and forts with his friends in the swamps near Georgetown, S.C. offered young Earl “Flynn” Trimnal excellent conditioning for the job he would someday assume in Vietnam – that of a “tunnel rat.”

“From the time I was about six years old, I wanted to join the Marine Corps,” Trimnal said. “My dad was in the Navy at Utah Beach in Normandy and I grew up wanting to serve my country. For three years, beginning in 9th grade, I worked after school, earning money to pay for summer school classes so I could graduate early. I wanted to get to Vietnam to help my country.”

The 17-year-old high school graduate entered the Marine Corps in October 1967. His training took him from boot camp at Parris Island to Camp Lejeune and then Camp Geiger for advanced training in the 106 recoilless rifle, flame throwers, and demolition. In Okinawa, Trimnal continued his training. The day he turned 18, he was on a plane to Vietnam.

Congratulations, You’re a Tunnel Rat!

Trimnal was assigned to the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, 26th Marines. “When I got off the chopper, this big old gunnery sergeant kept looking at me and scratching his head. I said, ‘PFC Trimnal reporting as ordered sir,’ and he said, ‘Congratulations, Private Trimnal! You’re our new tunnel rat.’”

During the Vietnam War, Communist guerrilla troops (Viet Cong) dug tens of thousands of tunnels, using them for intelligence work, and as effective hiding locations after ambushes. American “tunnel rats” were combat engineers on underground search and destroy missions — small, thin and highly skilled in hand-to-hand combat, armed only with flashlights, knives and pistols.

In the tunnels Trimnal found booby traps — grenades, mines and punji sticks — venomous snakes, rats, huge spiders and scorpions. Sometimes poisonous gases were used. “I lived in constant fear of not knowing what I would encounter or who I would meet with each foot that I crawled, knowing I could set off a booby-trap at any moment.

“They would find a tunnel and call me in. Usually they’d tie a rope to my foot, so they could pull me out if I got shot. Several times I had to throw a grenade because there were people back there. The life expectancy for a tunnel rat is about 7 seconds, but I was never injured while in the tunnel.

“A young Vietnamese boy showed me a lifesaving technique. He gave me a small glass mirror on a telescope, which could be angled in different directions. The VC would put curves in the tunnels for ambushes, or they’d dig deep holes and fill them with water, so they could hear us coming. I’d get to a turn and put the angled mirror down to see around the corner. Then lob a grenade in there. I still have that mirror. It saved my life many times.”

Out of the Tunnels to Reconnaissance

Trimnal excelled at tunnel work and was eventually transferred to  reconnaissance. He and his radioman, Calvin, scouted ahead of the battalion, gaining information about enemy activities in the area, avoiding direct combat and detection by the enemy.

reconnaissance. He and his radioman, Calvin, scouted ahead of the battalion, gaining information about enemy activities in the area, avoiding direct combat and detection by the enemy.

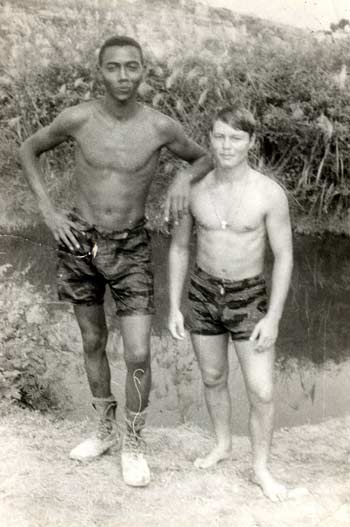

Trimnal has a photograph of the two men, one tall, dark and lanky, the other short, pale and compact. “They put us out in the jungle many miles ahead,” he recalled. “And while we were coming back we’d be cautious, always watching. If we saw movement, we would avoid contact, and call in artillery. Calvin and I went on many recon missions and we were pretty successful.

“One day the VC spotted us. I told Calvin, ‘let’s go,’ and we started running. They were lobbing mortars in on us. I was shorter than he was and I could get down lower. A mortar landed near us and messed him up pretty bad. Rather than leave him there, I grabbed him by the collar and dragged him up behind some rocks. The radio was still on his back, so I called it in. I kept talking and firing my rifle and suddenly, I heard a tank. I knew it was ours and it was a good sound. But Calvin didn’t make it. He died. He was from Wilmington, but I didn’t even know his last name.

“After Calvin died, I went crazy. I felt that he was my responsibility. He had done his job and I should have done mine better. ‘Crazy’ became my nickname. Everyone wanted to be with me because they knew I was there for business. I just didn’t care.”

Promotion to Squad Leader

After Calvin died, Trimnal was promoted to Sergeant and made a squad leader. “One time at 1:30 a.m. we were about 15 miles from our compound when they called us on our radio and said, ‘avoid contact if possible.’ They estimated 150 North Vietnamese regulars in our area. I pulled my men into a small thicket. I could see an enemy soldier’s feet and if he’d taken one more step, he would have stepped on my rifle. He stayed there for what seemed like 5 hours but was probably about 2 seconds and then he walked on. They never saw us. We waited until they got away, and then we called in artillery. The next morning there were at least 75 enemy dead.

“Our job was always to know where the enemy was, and to call it in. Sometimes with a squad, we would engage if we had to. But after Calvin, I felt my first job was to take care of my men.”

Three Times Wounded in Action

Trimnall was wounded twice and sent back into action. “The last time I was injured my buddies and I were ambushed near an Esso plant,” he said. “We pushed them back and then pulled a sweep to pick up bodies. I came across a VC in a bomb crater, but I’d run out of rounds in my magazine. I jumped in there and we did a bayonet shuffle. A log had flopped down, and he was against the tree. I bayonetted him, and it went right through to that tree. Another VC came at me and bayoneted me in the side. I reached in for my ka-bar (knife) and got him in the throat. I don’t even remember that. When I woke up, I was on the USS New Orleans and I thought, ‘I’m still alive.’ My 2 friends came up to me and said, ‘Hey you’d do anything to get out of the bush.’”

No Easy Transition Home

Trimnal recovered on the USS New Orleans during the two weeks it took  to get back to San Diego where he spent a month rehabilitating and two months of light duty. “When it was time to go home, I went to the airport, proud of my sergeant stripes and my medals. I was in my uniform with my sea bag. A woman came out of nowhere and spit on me and called me a baby killer. I turned around and went into the bathroom and changed into civilian clothes and I bought a first-class ticket home. I didn’t go on military standby. After that, I never wore my uniform off base.”

to get back to San Diego where he spent a month rehabilitating and two months of light duty. “When it was time to go home, I went to the airport, proud of my sergeant stripes and my medals. I was in my uniform with my sea bag. A woman came out of nowhere and spit on me and called me a baby killer. I turned around and went into the bathroom and changed into civilian clothes and I bought a first-class ticket home. I didn’t go on military standby. After that, I never wore my uniform off base.”

Like many other returning Vietnam veterans, Trimnal received no debriefing, no counseling, and no preparation for his return home. He found the transition back to “normal” life almost impossible; in fact, he camped in the forest for 30 days, eating squirrels and fish and trading for supplies. He distrusted the government, which had turned its back on him, and encountered numerous readjustment difficulties. Unable to obtain work in South Carolina, he moved to Florida. “I just didn’t care about anything,” Trimnal remembered. “I would ride 150 mph on my motorcycle and not even think about it. Just to feel the breeze over my hair.” After a failed marriage, Trimnal’s shattered life began a reversal when he invited a young woman named Jude to a South Carolina “Hell Hole Swamp Festival.” Although her friends advised against it, she accepted the date. They’ve been married for 26 years.

Getting Help for PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder, once referred to by terms such as “shell shock” and “battle fatigue,” affected approximately 30% of men and 27% of women at some point following their Vietnam experience. Many of our veterans, especially those like Trimnal who experienced high levels of combat exposure, continue to suffer the effects of PTSD. In effect, they are still living the war.

Trimnal’s symptoms were severe. “I tried to take AutoCad in college in Charleston,” he said. “It was near an Air Force Base and when those planes and jets would fly over, I’d flash back. The instructor’s mouth would be moving but I’d be hearing bombs and explosions and mortars going off and I could see the flashes. I had to drop the course.

“I didn’t want to admit there was anything wrong with me. I was a highly trained Marine. I felt ashamed that I’d been wounded – that I wasn’t a good Marine. It wasn’t until 1995 that I finally went to the VA hospital in Asheville. Every time someone came into the room, or dropped something, or a phone would ring I would jump. A psychologist asked me why I wore camouflage. I said, ‘I feel ready, alert.’ They took me to a room with a big round table with 8 people sitting around it. There was one vacant chair near the door. I picked up that chair and took it all the way around to the other side of the table and said ‘What do you want to know?’” After a brief conversation, Trimnal was told he had PTSD. “What’s that?” he said.

Trimnal and his doctors eventually found the appropriate medication which prevents agitation and takes the edge off for him. Most importantly, he joined a PTSD class. “Two other guys and I went through it all together,” he said. “We were supposed to dissolve after the class, but it helped us so much that we continued.” The Moral Injury Group meets every Monday at the VA. “I love them,” Trimnal said. “They’re my brothers.”

Advice for PTSD Sufferers

When asked what advice he would give to veterans suffering from PTSD, Trimnal replied promptly, “admit you have a problem. Then find help.” He added, “If you’re experiencing thoughts of killing people, of cutting their heads off and putting them on a stick in front of your house, you need to go to the VA.” Old feelings still crop up, but Trimnal has his friends and his counselor. And his faith. “I carried that grudge for so many years. Jude and I listen to Charles Stanley in the morning. One day he said, ‘for God to forgive you, you’ve got to forgive others.’ And I thought, ‘Oh my God.’ And the anger and hate left me, just like that.”

Coming Full Circle

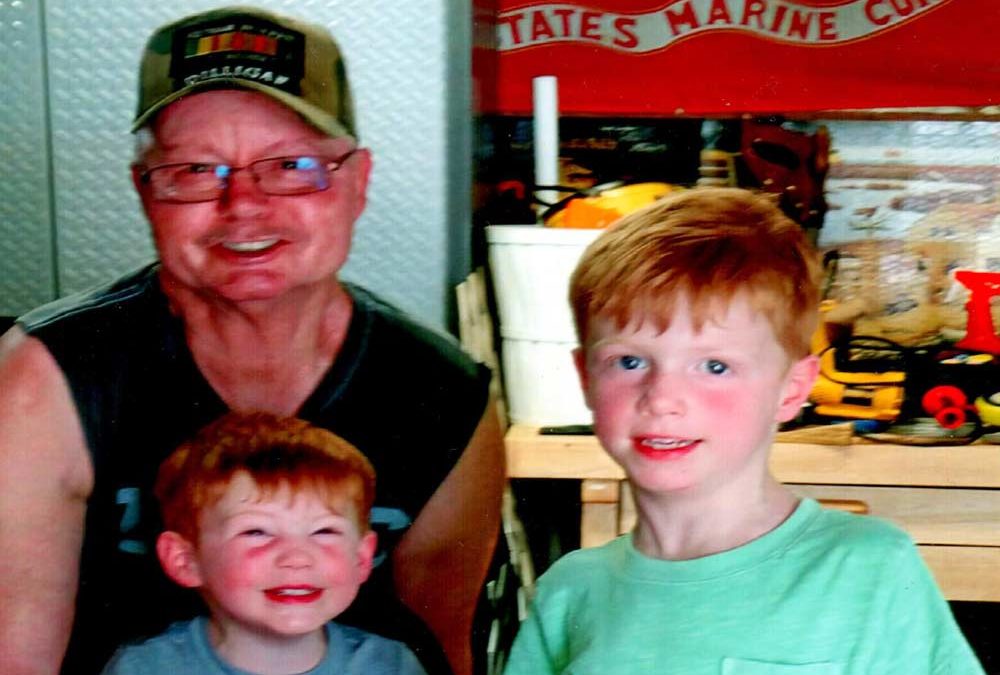

Flynn Trimnal’s story has several happy endings. His wife, Jude, is his best friend and advocate. “Sometimes it’s still hard,” she admitted. “But he’s a good man. When he has setbacks, he keeps trying and doesn’t give up.” Trimnal’s other constant companion, a 10-year-old Jack Russell mix named Penny, provides comfort and a calming effect when Trimnal begins to feel anxious.

And there is another Calvin in Trimnal’s life.

In October, Trimnal and 80 other Vietnam veterans took the Blue Ridge Honor Flight to Washington DC where they enjoyed a day of sightseeing and a hero’s welcome when they returned home. On the return flight to Asheville, each veteran received a bundle of letters written by friends and local school children, thanking them for their service. One of Trimnal’s letters was from an 8th grade boy named Calvin. Trimnal couldn’t believe his eyes. He responded to the young man and Calvin and his family sent the Trimnals a Christmas card. They’re now hoping to bring Calvin’s school class to Brevard to visit the Military History Museum. “I plan to stay in touch with Calvin, to follow this through,” Trimnal said quietly. “I feel as if everything has come full circle.”

To learn more about PTSD, treatment options, self-help tools and resources to help you recover, call 800-273-8255 and press #1 to speak to someone. It’s a Crisis & Suicide Prevention line, but they will direct callers to the assistance requested.

I was hoping to find out how many American tunnel rats from the Vietnam War are alive today in the U.S. My friend is one of them.

Help! My dad was tunnel rat in 68-69…he was doing great..but has spralwd into real depression. Anxiety etc. I’m trying to find him help!!!

My Tunnel Rat Team just had a reunion in Branson, Mo this year on May 18 – 21. 8 members showed up. I was on the first Tunnel Rat Team assembled in 1967 by the 1st Engineer Battalion Division. There are 3 members of that team still alive. Frank Gift of Maryland, Lt.Oatman of PA . Sgt. Baton (. Batman) that did over 4 tours and had a bounty on his head. We also have a have a special exhibit for the tunnel rats in the new 1st Infantry Division Museum that opened near Chicago .

Hi, Brent. I will contact Flynn with you question and send him your email address. I’m sure your friend has many compelling stories to tell. Thank you for reading Flynn’s story.

Michel Robertson

Author

Welcome Home, Brother

It’s an honor to have Flynn trimnal as a grand uncle…

He’s quite a remarkable and generous person. You’re lucky!

Thanks for the great article, its always affecting reading detailed experiences of soldiers… I find the Vietnam war to be especially captivating

Was there anyone over 5″11 that was a tunnel rat?