Vietnam Veterans Series

By Michel Robertson

On June 24, 1972, U.S. Air Force Captain David B. Grant was flying a mission  from Thailand into conflict-ridden North Vietnam when his F-4 Phantom took a direct hit and exploded. The fuselage was separating when both Grant and his “back-seater,” Bill, ejected through the fireball. They landed without injury, about two miles apart. They would not see each other again until days later when they became cellmates in the infamous North Vietnamese prison known to American POW’s as the Hanoi Hilton.

from Thailand into conflict-ridden North Vietnam when his F-4 Phantom took a direct hit and exploded. The fuselage was separating when both Grant and his “back-seater,” Bill, ejected through the fireball. They landed without injury, about two miles apart. They would not see each other again until days later when they became cellmates in the infamous North Vietnamese prison known to American POW’s as the Hanoi Hilton.

Grant and his father, Colonel A.G. Grant, share a dubious distinction. As a young lieutenant flying B-17’s during WWII, A.G. was shot down over Belgium and spent a year and a half as a POW in Stalag Luft I. A.G. and David are the only father (WWII) and son (Vietnam) to have been POWs from those conflicts.

Grant had not intended to follow so closely in his father’s footsteps; in fact, it was his father who advised him against becoming a pilot. Grant had graduated from the University of Chattanooga in 1965 when he learned he’d received his draft notice and immediately enlisted in the Air Force. “I wanted to be a hospital administrator, but because of a pilot shortage, they made me a pilot,” he said.

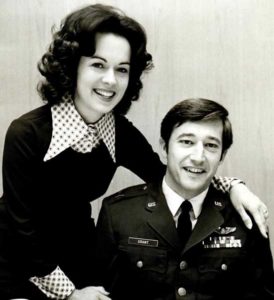

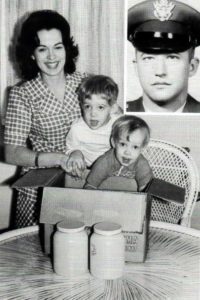

After attending Officer Training School in San Antonio, TX, Grant and his new bride, Betsy, moved to Laredo, TX, for flight training. Upon graduation, his group had orders for Vietnam. But in January 1968 the USS Pueblo was attacked and captured by North Korea. Vietnam orders were cancelled, and they went to Japan.

There Grant met Lt. John Barker, now of Brevard, and was assigned as his GIB (guy-in-back) flying F-4 Phantoms. “John had a huge influence on my flying career,” Grant said. “We spent about 70% of our time in South Korea.” From Japan, Grant returned to MacDill AFB in Tampa where he upgraded to Aircraft Commander (guy-in-front). Once again, he received orders to Da Nang which were changed, and the Grants went to the Philippines.

Flying Low from Da Nang

In 1972, President Nixon authorized increased air strikes on North Vietnam targets. “Our assignment in the Philippines was curtailed and I again had orders for Da Nang,” said Grant. “I had seven days’ notice to get Betsy and the boys back to the states and depart,” said Grant. “I arrived in Da Nang on April 1, 1972.

“Flying from Da Nang was rewarding from a pilot’s point of view. We were doing a lot of close air support for our guys and using ordnance that required low-level delivery for accuracy. Flying at 1,000-2,000 feet, we could smell the gun smoke and watch the enemy scattering or even shooting at us, even though we were going 450 knots. When successful, we got some rewarding calls relayed back through the forward air controller that said ‘Thank you! You saved our butts.’

“I had one mission where the North Vietnamese Army were on the 2nd floor of a plantation house. They had our guys pinned down in the front yard behind a stone wall. From my plane, which was level with the 2nd floor window, I was able to strafe and clear the enemy from the building. I was so low that my jet’s exhaust dusted our guys.”

Captured and a Painful Journey

In June 1972, Grant’s wing moved from Da Nang to Takhli, Thailand. He and Bill, his GIB, were shot down at 4 pm on their first mission out of Takhli, about 40 miles from Hanoi. They tried to shoot me as I parachuted down and were fairly close when I landed, so I hid under a very dense bush on a steep incline. I dug in a little so I wouldn’t slide down. I spent the night that way, with creatures crawling all over me. The North Vietnamese were less than 50 yards away.”

In the morning, the enemy began their search and found Grant’s hiding place. “They did a ‘ready, aim, fire’ and 5 to 7 of them shot into the bush,” Grant said. “Then they waited. Then another ready, aim, fire. One shot hit me in the foot. They came into the brush and were shocked that I was alive when I rolled my head around and looked up at them.

“My arms were tied in back around a bamboo pole. I had a hole in my foot and hadn’t had any water. Then we started a hike. This was June in the jungle and it took about 4½ hours to get down the mountain. In the villages, they stirred up the crowd and the villagers struck me with sticks and rocks. Eventually a militia guy took over and beat me up. Then he stuck his automatic between my eyes and pulled the trigger. It clicked. Another mock execution followed.

“We continued through villages. In each one I was beaten. Finally, we arrived at a larger village where they held a night-time kangaroo-court trial. I was on my knees with a bayonet on either side of my head and I made the mistake of smiling at the woman who held one of the bayonets. She made sure the blood kept seeping from my temple. I was convicted as a war criminal and thrown into a little hut. They gave me some slush with rice and fish that was hard to keep down.”

The next morning, Grant was released to the regulars who put a bag over his head and tossed him onto the back of a truck for the journey to Hanoi. The road was in terrible condition and each bump and jostle brought agonizing pain to his injured foot.

Heartbreak Hotel

In Hanoi, Grant’s arms were finally cut free and he was thrown into a small room. “I stayed on the floor,” he stated. “After four days of interrogation and beatings, I was put in a small cell in the section of the prison called ‘Heartbreak Hotel.’ The dingy 5’x 7’ cells held two concrete slabs with shackles on the end. I lay there with no idea where I was, but it must have been Sunday because I heard some Americans singing.

“I hopped or crawled wherever I went, and the guard, unsympathetic because it slowed him down, ‘encouraged’ me with his rifle butt or his foot. The entire time I was there, nobody ever addressed my foot. I received zero medical help.

“Because I couldn’t walk, they put Bill in with me. Bill had lasted in hiding one day longer than I had. We were together the rest of the time. After about five days (which seemed like 2 years) after I was captured, the guards told us to put on our long pajamas. They tied us up, put bags over our heads, and took six of us to a news conference.”

At the news conference, Grant was given a small towel to wrap around the filthy rag on his foot and a crutch which proved useful in more ways than one. “Eventually, I was able to walk on my heel,” said Grant, “but I was faking that I couldn’t walk. I got very fast on the crutch. I put the crutch against the wall and climbed on it to reach the bars where I used hand signals to communicate with guys across the way. Bill watched the door, and if he spotted a guard, he’d get in his area quickly and I jumped down, grabbed the crutch, and did the same.

“By the end of July my leg was discolored up to just below the knee, with long grey/green streaks. My foot was huge and a strange color. I think the interrogations may have helped, because the enemy started each interrogation by stomping or jamming anything that was injured. That kept my foot bleeding and may have helped clean the wound, because the water was filthy. Finally, a guard gave me two small white tablets and eventually the infection subsided.”

Eating and Staying Sane

Eventually Grant and Bill were moved to a larger room with other POWs.  They received two small meals a day. Breakfast was tea and a half loaf of bread. “The bread had things in it, like bug parts and rat poop,” Grant said. “We everything because it was probably the only protein we got. The tea was a little bit of dirty water and maybe a tea leaf. In the afternoon we received tea, another piece of bread and a bowl of soup. The summer fare was pumpkin soup. I knew it was pumpkin because they were stored on the floor in our room. Huge rats gnawed at them and they became moldy. The broth orangish water. A shred of pumpkin in your soup was a treasure. You’d look at it and say, ‘filet mignon!’

They received two small meals a day. Breakfast was tea and a half loaf of bread. “The bread had things in it, like bug parts and rat poop,” Grant said. “We everything because it was probably the only protein we got. The tea was a little bit of dirty water and maybe a tea leaf. In the afternoon we received tea, another piece of bread and a bowl of soup. The summer fare was pumpkin soup. I knew it was pumpkin because they were stored on the floor in our room. Huge rats gnawed at them and they became moldy. The broth orangish water. A shred of pumpkin in your soup was a treasure. You’d look at it and say, ‘filet mignon!’

“Most days included 5-10 minutes outside where we’d scoop the mosquito larva off the top of a horse trough and pour cold water – no soap — on ourselves with a bucket. We washed our shorts and put them back on again.

“For entertainment, we recounted our histories. As we got more people, we held classes and played games such as Jeopardy. We took turns telling stories, which was my favorite activity. Generally, it turned out to be about a date we’d had in our home town: how we picked her up, where we went to dinner, what we’d had to eat. Eventually, the guard ordered us to go to bed, ddbut the light always stayed on. To this day, I can’t sleep with the light on.”

Keeping the Home Fires Burning

During Grant’s imprisonment, Betsy coped at home. “I had the easy job,” Grant insisted. “All I had to do was stay alive. Betsy had the hard job of caring for two small sons, tending the home alone, and worrying about me.” Betsy responded modestly. “We were blessed to know that he was alive within five days. I was fortunate at home in Chattanooga, lovingly supported by family, friends and church. And, as his grandmother said, we waited with “bated breath.”

Release and Homecoming

In mid-December 1972, with the failure of peace talks, President Nixon announced the beginning of a massive bombing campaign. “The first mission was December 18,” said Grant. “We called them the Christmas bombings and we finally knew that there was hope.” The bombings continued until the North Vietnamese agreed to resume peace talks. The Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973. From February to April missions departed Hanoi, bringing the POWs out. Groups of POWs were released based on longest length of time in prison and medical condition. Grant’s flight home was second to last, departing Hanoi on March 28, 1973.

“They put us on a bus and took us out to a C-141. We were all very antsy, knowing that they could stop the release of even shoot us down. Nobody was comfortable until we were over the water. Then it was great.”

On Grant’s previous trips home, he’d encountered strong antiwar sentiment as he flew into San Francisco. His last trip was different. The POWs were flown to the Philippines for medical treatment and debriefing. Grant was greeted at Clark AFB by former squadron members, including his cousin Rhae Mozley and her husband Don (now of Brevard). After several days of rest, they returned to the U.S. in new uniforms to a heroes’ welcome, including a lot of yellow ribbons.

Aftermath

Grant remained in the Air Force after the war, retiring as a Lt. Col. in 1994. He and Betsy have three sons, David, Stephen, and Robert, and seven grandchildren. Their favorite activities are family-focused, including “Cousin Camp” when all the grandchildren come for a visit.

When asked about PTSD, Grant answered, “I suppressed it. If I got into pressure in my job, I’d go out into the garage and lie on the concrete and think ‘things aren’t so bad.’”

In the Grant home, a brass plaque is engraved with sentiments that husband and wife hold dear to their hearts. It reads: You have never lived ‘til you have almost died. And for those who fight for it, life has a flavor the protected will never know.

Article by Michel Robertson

Published in the Translvania Times on October 8, 2018

In collaboration with writer Michel Robertson and the The Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas, The Transylvania Times will publish an article once every two weeks on a local veteran who served in Vietnam.

I wore the Lt. Col.’s POW bracelet for about 5 years, until he came home. I was just a a little girl then and lived in Chattanooga, TN. I prayed for him every night. My own dad was in Vietnam as well. I remember crying when the Lt. Col. , who was a Captain at the time, was released.

I have my Mom’s POW bracelet with Capt. David Grant’s name and the date 6-24-72 inscribed on it.

I have my mom’s (Joan Nicoll) bracelet with Capt David Grants name engraved on it I was always under the impression only one bracelet was released for each veteran I posted the bracelet on FB today snd was immediately sent this article by a friend What an amazing story. Thank you for Your service Captain Grant

Thank you for your comment. I’ll make sure David Grant sees your remarks. I’m so glad to learn your mother had one of his bracelets.

Michel Robertson

Author

“Welcome Home, Brother”

I still have Capt.David Grants pow bracelet dated 6-24-72.I was 14 years old when I got it and wore it until I read in our hometown paper The Daily Times in Salisbury Maryland that he had came home.I am 64 now.Thank you for your service Capt.Grant.

I served with Dave Grant at Shaw AFB until he retired in 1994. Like I told him on his retirement day, it was a distinct privilege to have served with him. He was one of the single best officers I have ever served with in my 26 year career. A hero on so many levels!

I got my Capt. David Grant 6-24-72 bracelet in my mid 20s and I am now 73 and have kept it all these years. I am giving my bracelet and this amazing article to my 22 year old grandson for Christmas 2021 so he will have a piece of history during the Vietnam era. I have two brothers who were in the navy and also served in Vietnam. I have thanked them for their service and am grateful they both came home safely. Thank you Capt. David Grant for your service and your sacrifices while serving and defending our country. God Bless America!

I was Dave’s roommate for about week at Takhli. Quite a shock to learn he had been shot down. I packed up his stuff and wrote a letter to his wife. Many years later we reconnected at a Rats reunion. He smile was just the same as always.