An Interview with Korean War Veteran Bill Lack

By Mike McCarthy

I grew up in Meridian, Mississippi and my father and mother were divorced in 1940. My father was automatically drafted into the military before WWII started. Then his two brothers got called in after he did. My father and uncles all being in the war, I started reading the newspapers and listening to the radio and keeping books on them and writing down, making notes, and all kinds of stuff.

Just 15- and 16-Year-Olds

I just became very interested in the war, and we did everything we could to help. A lot of my friends were doing the same thing. We got a wild hair one time. We heard about the National Guard. Six of us that were age 15 and 16 decided we would see if we could join the National Guard, and we did. We joined the Mississippi National Guard and everything was working fine. We were going to meetings and then we went to summer camp.

While we were at summer camp, the Korean War broke out. And that changed the world. My company commander did so much. His name was G.V. Montgomery. He went by the name of Sonny Montgomery. He [later] ran for congress because they were not taking care of the Korean War veterans. And he ran for congress on, “Elect me and I will fix it.” And fix it, he did.

Commander Sonny Montgomery and the G.I. Bill

He wrote the G.I. Bill that we have today. He got it passed. It’s named after him: the Montgomery G.I. Bill. He was my company commander and I was his driver for a while when I first went into the Army.

He was a Captain when I first went in, but he retired from the military as a Major General, two stars. He was a very opinionated person. Knew the constitution, everything you ever wanted to know about the constitution. But he said, “We take care of our veterans.” But for the Korean War veterans, they said there was no war, so you can’t get VA privileges. WWII veterans went to the VA but we couldn’t, because it was never a declared war the way Harry Truman did it. It was a big, big, big problem for us.

Breakfast with Presidents

Montgomery went to battle for us and stayed in congress a long time. When he died, every single president except Ford (who was in the hospital) came to his funeral. I was one of the pallbearers at his funeral, and I got to have breakfast with all those presidents.

But the thing that really got me going was that company commander, Sonny Montgomery—Gillespie V. Montgomery. He was my hero.

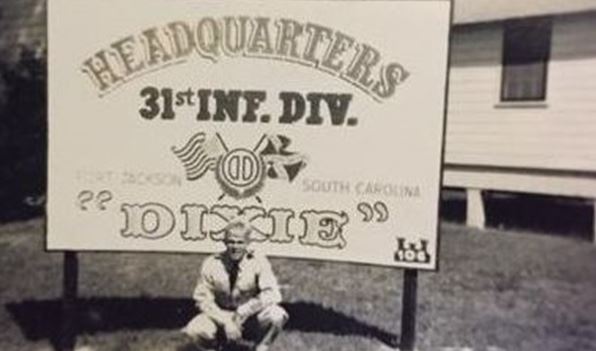

While we were at summer camp, our unit, the 31st Infantry Division—that’s the Dixie Division—was one of the most famous divisions in the U.S. Army. It goes back to World War I.

Above, Bill Lack at Ft. Jackson, S.C. in 1951

Then the Chinese Came Into the War

Then when the Chinese came into the war, they called two more divisions in. We got notified on December 15, 1950, that we were called to active duty.

When I joined the National Guard, I was actually fifteen. I gave my age as seventeen and got my sister to sign my mother’s name. When we got called to active duty, things got a little tougher, so I confessed up. I said, “I really wasn’t seventeen, I was only sixteen, but I’m seventeen now.” Nobody cared. They let me go and I went ahead to Fort Jackson.

Sonny Montgomery had become the aide to the commanding general. He switched me over to work at Fort Jackson with the MPs, even though I was in the tank battalion. Then I was sent to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, where we taught R.O.T.C. students from colleges in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, and North Dakota. They flew our unit out to work on a movie about WWII tank battles. We supplied the tanks for that.

Out of the Army

Back at Camp Atterbury, I was discharged from the Army. My time was up. I went to school at Mississippi Southern College with the intention of boxing and playing football.

I went home for Christmas. That’s when the roof fell in on me. I just didn’t feel right. I prayed, talked to God. I just was unhappy, just didn’t feel comfortable. I went in and gave my mother a hug and said, “You’re not going to believe what I’m telling you, but I’m going down and enlist in the Army and tell them this time I want to go to Korea.” She started crying. I said, “But I have to.”

Above, SGT Bill Lack in Teagu, Korea in 1953

on assignment with Prisoner of War Command

In the MPs Again

So I want down and re-enlisted and because of my experience, they signed me up in the MPs. I went to Fort Jackson first, and then to the Seattle area. The war was very bloody at that point. They took a lot of the ones who had been charged with minor crimes and put them on ships going to Korea. I got upset about that.

Prisoners

That still wasn’t what I’d signed up to do. I went to the colonel and told him. He said, “I know that. You’re going to Korea in four days.” So I boarded a ship and we went to Camp Drake in Yokahama, Japan, where I trained for three weeks. They reassigned us to Korea from there. Thirty-two of us were assigned to headquarters of the prisoner-of-war command. There had been a lot of problems with the Korean War prisoners.

They had a general who stupidly went into North Korea and they held him as a hostage. They got him back and he was drummed out of the Army after that for being stupid enough to do what he did.

Above, linguists in the Military Intelligence Unit who spoke Chinese, Korean, and Russian

We were trying to fix all of this. We had eighteen prison camps with all kinds of prisoners in them. We put all the real problem Koreans in Koje camp and put the Chinese prisoners in Cheju-do, another camp.

About half of the ones in the North Korean camps were not North Koreans, they were South Koreans that had been drummed up and put into the North Korean Army as the North Koreans came south on that first big charge.

Above, 500th Military Intelligence Unit of the US Army in Incheon, Korea. These men worked for Bill Lack as interpreters in the languages of 15 countries.

We had to go in there and sort these prisoners out and put them into communist and non-communist camps. South Korea would never sign anything because their people had gone to North Korea. We spent weeks emptying out one prison and then filling them up, getting the right kind of groups together.

As this was going on, the shooting war was still going on. All of a sudden one day, all hell broke loose. They had taken the U.S. guards off the towers and put South Korean guards up there, but had failed to give them any ammunition for their guns. They were all of the non-communist prisoners.

They Broke Down the Prison Fences

The prisoners hit the barbed-wire fences and broke them down. We lost 135,000 prisoners. Someone asked the colonel, “What are we supposed to do?” He said, “It’s simple. Don’t shoot anybody, but each one of you go out and grab five of them and bring them back.” Of course, we didn’t get any of them back. Once I was going through the lunch line and I saw a couple of people serving who looked like prisoners who had escaped. I asked the colonel if he had recognized them. He said, “No, I didn’t, and you didn’t either.”

Ceasefire

Two days after that, they signed the ceasefire. Then we diverted to Incheon, doing the prisoner exchanges. Some of the prisoners had been brainwashed and did not want to go back home. We worked on persuasion teams, we called them. We got things from their mothers or their kids and passed them on to these prisoners to try to convince them to come home. None of that was successful. We didn’t get any of them to come home.

We basically asked them, “Where were you?” “How were you treated?” “Did you notice anybody wearing military uniforms?” “Where did your food come from?” We tried not to confuse it with military information, just, as a human being, “How were you treated?”

Most of those were Chinese and uneducated, some had difficulty reading. Those who refused to go home were Chinese, Russians, and North Koreans. We had a certain number of days and weeks we were allowed to work with them. They were still in the custody of the North Koreans.

We interviewed them in the DMZ. At the end of the day, we went back to our side and they went back to their side. I think we got a total of three to agree to go back to their homes. The brainwashing was unbelievable. Why didn’t they want to go home? We think it was because they were treated very nicely. They were given better food than the other prisoners. Very little publicity was given to this.

Mapping the DMZ

Then they moved us over to determine where the actual border was going to be. There were no natural borders, just the 38th parallel, which is an imaginary line that didn’t really mean anything. We were negotiating with the North Koreans, little sections a time. We moved it so that we had natural things like mountains and rivers to determine where the border was. Things that would prevent people from accidentally walking across the border.

Above, MSG Bill Lack in Japan in late 1955

After Korea, I got orders that I was going back to the language school in California to learn the Russian language. So I started scaling down and getting ready to do that. I got on a plane to go to Japan and was supposed to fly from Japan to California. But I only got as far as Japan. There, I found out I had been re-assigned to be the Acting Sergeant Major of the 500th Military Intelligence Group (MIG) at North Camp Drake (A.K.A. Little Pentagon), Japan. That was the headquarters of our MI in all of the Far East.

I found out that I worked in the office with a man I had served with, Captain Wakuya, who was from Hawaii. He was the one who had recommended me for this job. There was a woman civilian employee working as a secretary there. She was Corinna Boyer, from Columbus, Ohio, nicest lady I ever met in my life. We got to be pretty good friends

My Future Wife Appears in My Office Chair One Day

One day, I came back from lunch and another young lady was sitting at my desk. The secretary and the young lady both looked embarrassed. Finally, the secretary introduced the young lady, “This is my daughter, Beverly.” It just blew my mind. I didn’t know what to say. The secretary looked over at her daughter and said, “After today, I guess you’ll have to start bringing three lunches instead of two.” Beverly and I started dating and we had a big church wedding in Tokyo with 135 people attending. Beverly and I stayed married until she died two years ago.

After our honeymoon, I found out I’d been transferred to Headquarters Far East Command. J2 Division, Special Projects Branch, and promoted to Master Sergeant.

We covered the entire Pacific Rim. I did a lot of traveling and published a book every month and sent it to the President and all the heads of military. After we printed it, we destroyed it and melted the printing plates down. These books contained information about what was occurring in the entire Pacific Rim. I stayed in that job from 1954 to 1957.

Out of the Army–Again

I had committed to my wife that when we had children, I would get out of the Army, and that’s what I did. That first child now lives right down the hill from me and is a veterinarian at her own clinic. In my dream, I had wanted to be a veterinarian, but I couldn’t afford college and medical school and all, but she went. She was born in Japan in a Japanese hospital. Beverly and I had four more children.

I went to Jackson, Mississippi to pre-med school to be a veterinarian. I was going to school and working. When we had our second child, I told Beverly, “There’s no way I’m going to be a veterinarian.”

I went to work for Sears and put in 20 some-odd years. I went to work with Western Auto in Little Rock, who was in the process of buying four companies in Texas. When Sears merged Western Auto into Sears, I took early retirement. I also worked for Advanced Auto Parts.

I was offered a job in Egypt and Israel with Multinational Forces Observers in the 1970s. The U.S. had created an organization within the U.N. that became a 28-country group headquartered in Italy. I went first, then my family came over to live also.

Tragedy

Our family went on a safari to Kenya during the gator mating season. A lot of people were visiting, including a group of Japanese tourists right behind us. About five days after we got home, my 14-year-old daughter got sick. We took her to a hospital in Israel. Apparently, one of the Japanese tourists had been bitten by a mosquito, which, in turn, bit her. She died after 17 days in the hospital. She had gone to school to study Arabic and became fluent in only three weeks. After she died, we came home.

My current wife, Sandra, and I live in Candler, N.C., near Asheville. It’s the best place I know of because of the warmth of the people here.

At right, Marilyn Monroe came to perform in Korea. Approximately 150,000 soldiers were positioned on the mountaintops to get a look at her. Some soldiers were 10 miles away, using telescopes. Photograph courtesy of Bill Lack.