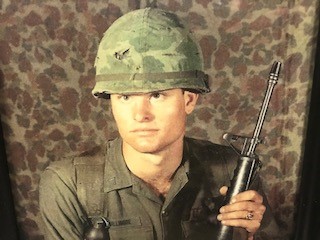

Above, Hallimore (standing, 2nd from left) with buddies

In part one, Hallimore described search & destroy missions, “bunker-busters,” and life in the Vietnam Delta.

One Fires, We All Fire

Part 2

by John Hallimore

Our armament would typically consist of a machine gunner, a soldier with a 60mm grenade launcher, and 6 regular riflemen including the squad leader and RTO (radio telephone operator). We had concussion grenades to throw in the water should the VC jump or fall from their sampans and we had claymore grenades propped up on each flank of our ambush; should someone try to surprise us by approaching on land from the right or left.

The claymore would best be described as a flat curved rectangular-shaped directional grenade that was set on the ground and then remotely detonated. It would explode, throwing a thousand ball bearings out and away from us; just an extra bit of American firepower security. We also had flares should we want to light up the sky or mark our location if air power assistance was requested.

Generally, the squad leader would initiate the ambush by being first to fire; instantly followed by all of hell canceling the serenity of the jungle night; now turned into the deafening chorus of bullets and grenade explosions punctuated by the yelling and profanity of American warriors doing battle.

Where’s “Charley?”

War, and its microcosm of ambush activity, is generally not synonymous with what most of our friends or family contemplate or imagine. There is a lot of down time. Even though three separate ambushes were set in place each night by our infantry company; Charley (the VC) may not be seen for up to 20 or 30 days.

Complacency then becomes one of the biggest enemies of the soldier. Sitting and waiting in the dark becomes very unnerving. It is difficult to see, trees start to move and objects can appear on the water and then vanish. The mind needs something happening or something to think about. The nights become torturously long just staring at nothing, not making a sound and trying not to move.

There’s No Time for Confusion. . . or Coffee

We would be lying in the prone position teamed up so half of the squad would sleep and the other half would be awake, watching and waiting. Your partner better not fall asleep nor start nodding off during his watch, and you better not snore or make noise if you are able to sleep for a wink. When the communication string is yanked, you better be ready for action. There is no time for confusion (and surely not an American cup of coffee to wake up or stay awake, HA!). The aroma, a squeak or glitter of light could set off “An Ambush Gone Bad.”

In jungle warfare, it is probably more often than not that the infantry soldier does not know where the bullets are coming from. He can hear the booms from the weapon and if the bullet goes by closely, he hears a “crack” in the air. At night, you might see the flash from a weapon’s muzzle. Hopefully upon initiation of the canal way ambush, we all have a specific target to shoot. But the opaque jungle, particularly when shrouded in darkness, hides everything very quickly. It provides the perfect cover for both sides of the conflict.

We Took the War to the Enemy

Nevertheless, whether being able to see the enemy or not, the U.S. soldier has plenty of ammunition and he will provide or return an awe-inspiring amount of firepower. If shot at, we fired back. When springing the ambush, we naturally fired first with everything that we had, inflicting casualties and intimating the Viet Cong.

We took the war to the enemy and I am certain that it affected their nighttime travel plans. Ambushes didn’t last very long unless we were to make contact with a superior sized force (unrealized in the initial observation). If the firefight continued, we would then set off the claymore grenades, pull back, and call in air power for an even greater display of firepower and destruction of the enemy.

“If one soldier fires, we all fire.”

This was true whether we actually saw the enemy or not. One of my friends on a night ambush said that a snake came right towards him just beyond the muzzle of his rifle. It stopped and stood up like a cobra. He was scared to death and wanted to blow its head off. But he knew if he fired, the ambush would be initiated with full force. He didn’t shoot. I don’t remember the rest of the story; I guess the snake went away.

There were times after entering a firefight and shooting multiple clips of ammo, that we would stop and try to figure out who shot first, why and what we were shooting at? In a few instances, no answers would emerge, providing a humorous moment of realization in what otherwise was a tense action of combat.

The amount of firepower exhausted in a firefight had to intimidate the non-comparably equipped VC combatants. The VC units as contrasted to the American fighting machine would fire and run or they may lob 15 or 20 quick mortars at our location and then they were gone. This was hit and run jungle warfare. Survival was important to both sides.