Private Bradford Freeman of Caledonia, Mississippi and Colonel Ed Shames of Virginia Beach, Virginia are the only two living members of the

“Band of Brothers” 101st Airborne Division, WWII.

An Interview with Bradford C. Freeman

By Janis Allen

Brad Freeman was one of eight children who grew up working on their daddy’s rented 410-acre farm near Artesia, Mississippi, black land. They grew cotton, corn, hay, and cattle, and operated a dairy farm. Brad was an 18-year-old freshman at Mississippi State studying agriculture when he was told that if he joined the Army he could avoid being drafted. They let him finish out that year.

Bradford and his brother had always wanted to become paratroopers, so they both joined up. Brad entered the U.S. Army on December 19, 1942. His brother was sent to the Pacific. After training at Camp McClellan, Alabama, Camp Shelby, Mississippi and Camp McCall, North Carolina, he was sent to England to join the 101st Airborne (who were already there): E (“Easy”) Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment. This is the unit portrayed in the 2001 movie “Band of Brothers.” This is his story in his words.

“We were at a camp in Alderborne, in southern England on June 5, 1944. They had us under guard until they told us when we would go. We were supposed to jump the 5th of June, but it was raining and they cancelled it. We jumped at midnight on June 6. We were one of the first three planes. I was in the mortar squad. My job was to carry the base plate of the mortar. SGT Malarkey was my squad leader. He carried the other part. We were on maps. I set the sights. We had three other boys who carried the ammunition.

“I landed in a pasture where there were beautiful white-faced cows. I was told that when I got there I was supposed to stay right where I was and wait till I got somebody else with me. I saw a man come down. He was my buddy, Lewis, from Atlanta, Georgia, and he had broken his leg. I helped him into the bushes and I took his things and put them in the woods. We were supposed to help a fella if we could, and then go, because we had something else to do. We had to get the big guns. I went on and joined some other boys and we gathered at a place. We were popping our little crickets to keep from shooting each other or getting shot at.

“We had to take the place and get the big guns so they couldn’t interfere with the soldiers who were coming ashore at Normandy. We scattered pit and set up. We were taking roads and bridges. They had told us that if we saw an enemy truck coming down the road, to shoot the driver. We happened to be fortunate enough to do it right, I reckon. We secured the area and let the Army go through. They had come ashore and now they got on with their business.

A week or so later, General Eisenhower wanted us to take a beach town on a peninsula in France that the Germans occupied. It was a place where landing would be a lot easier than landing on the beaches. It was surrounded by water. There was no way to get to it but a concrete bridge—one way in, same way out. We were firing mortars into that town. We finally took the town.

We went back to England and did more jumps. We were loaned to the British Army. We jumped for them in Holland on September 17, 1944 [Operation Market Garden]. The Germans came right on down the river and blew the bridge, so we had to turn around and go back. We saw the Dutch people taking girls who had associated with the Germans and cutting their hair off. We laughed at that.

We went to Bastogne when German tanks came through. When a German plane came over, we would stop and stand still like a fence post. We heard the Americans were losing and giving up and that was a sad thing for us. We were told to run, but we took off after the Germans. One of our fellas, a short, little guy about five feet, “Babe” Heffron, told them, ‘We’re from the United States of America, we’re going to do whatever we want to.’

“When the Germans found out we were the 101st, they stopped. When they saw the eagle on our shoulders, they stopped. They knew who we were, yes ma’am. We waited for the Americans coming on up. We set up our mortars and were supposed to take three towns.

“During the Battle of the Bulge, I got shot in my right leg near Neuville, France. It didn’t hit the bone, but it cut a leader in my leg. I couldn’t control my foot, but I could drag it along. They said I got shot by a ‘Screaming Mimi.’ You could hear it coming, but you can’t get out of the way. They said it was a little boy who did the shooting.

“Then there was more shooting. We tried to get out of the way and took cover between two dead mules. They was froze solid and boy, they were cold! That was all the mules I seen in all of Europe. A Jeep picked us up and took us to town.

“Another fella, Ed Joint, got shot in the arm. The medic came and started cutting my britcha-leg. I told him, ‘You take care of the other boy first. I’m not hurt.’ But I was. The medic couldn’t do anything for the leader in my leg, so they flew me to England, where I stayed for three months before they could get the leader to grow back to where it would stay. I got back into the fighting. Now, I can walk on two feet.

“We were near Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest when the Germans surrendered. I was guarding a bridge nearby. The Germans were coming up and we were guarding it. We got a new bunch of soldiers in and we were training them.

“Some of us were assigned to load horses into train cars. Every other car had horses and the cars between them had displaced persons. We rode on the ends of the car as guards. We got off at one of the stops and didn’t go all the way, so I don’t know where they ended up. They sent a truck to pick us up.

“That was the end of the war for us. After the war was over, we stayed in a house in the mountains and went hunting. We had somebody to cook for us and somebody made up our beds. I hunted quail because that’s what I had hunted in Mississippi.

“When the bomb fell, I could have gone to Japan, but I had enough points, so decided to come back home. They sent me down to Marseille, France, where they were shipping people home. The ship I was supposed to get on sank. They kept me there for two weeks, and I was ready to shoot them!

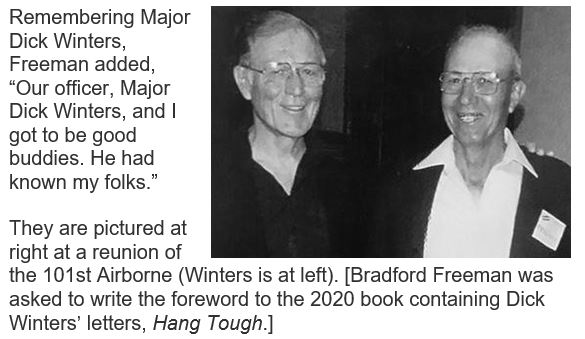

“Our officer, Major Dick Winters, and I got to be good buddies. He had known my folks.” [Bradford Freeman was asked to write the foreword to the book of Dick Winters’ letters, Hang Tough, published in 2020.]

“When I got home, I went back to farming and also became a mail carrier for 32 years. My brother also got home safely from Japan. I married a girl I used to play with when we were five years old. Her name was Willie Louise, and we had two beautiful daughters. My wife passed away in 2008.”

When “Mr. Brad” was thanked for what he did to save our civilization from Naziism, he said, “I was glad to do it and was glad I could do it.”

Asked if he was ever scared when jumping out of a plane, he said, “No, we were trained for it and we went there to do it. And I had packed my own chute.”

Pictured left, Tom Hanks and Bradford Freeman (at right) attended the funeral of “Band of Brothers” Captain Dick Winters. Pictured right, the United Kingdom’s Prince Charles shakes the hand of Bradford Freeman in London.

Thank you Mr Bradford Freeman for all you did for our country you served well🇺🇸

What a man, thank you for your service sir.

Mike England,

You said it perfectly!

Mike,

Your words “said it all.” Thank you.

My condolences to your family and friends, along with my thanks for your service. I’m a Mississippi girl, myself.

Rhonda,

Your kind words speak well for our country. Thank you for your respect and appreciation.

Rhonda,

You speak so well for many of us. Thank you for your appreciation.

Thank You Mr.Bradford Freeman For Your Service to Help Keep Us Free.My Dad was in WW11, I Can Still Remember When He Came Home, I Was 6 Years Old. I Am 82 Now.

As a history teacher at Oak Grove High School in Hattiesburg, MS, I show parts of Band of Brothers after we complete our WWII unit. I always mention our Mississippi member of the Band of Brother, Mr. Freeman. Words are not sufficient to express our gratitude to all of the men and women who fought bravely during World War II, but I want to make sure that the next generation is aware of the price of freedom. Thank you!

Growing up in NYC late 60’s-1970’s…….there were plenty of WW2 vets in the neighborhood, from church, team coaches. I remember some turning 50 and thinking that was old. Some had limps and other ailments related to military service but they, and we, just took it in stride. My dad was a Korea vet and had seen serious combat. Now April ’22, I don’t think a single one of those veterans is still around. They all had a hand in raising us, become responsible adults, some of us served ourselves. Florida probably has the most living WW2 vets now, and whenever I come across one it is my pleasure to meet and trade some shop talk with.

Very descriptive blog, I loved that bit. Will there be a part 2?

I think this is among the most significant information for me.

And i’m glad reading your article. But wanna remark on some general things, The web site style is ideal, the articles is really excellent : D.

Good job, cheers

my web-site :: korich168

Thank you for your service sir. May you rest in peace.

Rest in peace sir. You’re the last man entering the final reunion of Easy Company, 506PIR. Please send them our best and tell them they will never be forgotten.

Thank you, Mr. Brad! You are a true hero!

Rhonda,

Your kind words speak for all of us. Thank you.